Author: Florian Coldea

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.1.2

Abstract

The subject of hybrid threats has been in focus for some time now, for both academia and practitioners in various security and defense-related fields, but research is still unfocused enough and opinions yet too divergent to allow for a joint understanding of the term, as is the case with other terms in the sphere of security, too (the easiest to mention being ”terrorism”). Our lack of a common understanding of the phenomenon with our closest allies is inevitably a weakness, in a world where many categories of threats are closely interconnected and tend to transgress physical and virtual borders alike. Therefore, the need for a closer look at the concept is bound to lead

us to more effective approaches in handling the consequences of hybrid threats.

us to more effective approaches in handling the consequences of hybrid threats.

Keywords: Hybrid warfare, Intelligence, Hybrid Threats, Intelligence cycle, Russia

Threat. Hybrid Threat, Hybrid War. Conceptual delimitations

In intelligence, threats constitute actions, facts, states, capabilities, strategies, plans with an impact on national security objectives, values and interests. They are, usually, firmly delimited from risks and vulnerabilities, and can be internal or external, traditional, asymmetric, hybrid, conventional or non conventional, traditional or non traditional.

Expanding our view to encompass hybrid threats, they do not significantly divert from the meaning we give threats in intelligence, but rather expand the range of objectives, values and interests to be defended. The concept of hybrid threats itself derives from that of hybrid warfare, which is by no means new, but rather easier to define by comparing it to other two generally accepted terms, that of classical and that of asymmetric warfare.

Thus, traditional or classical warfare, as coined by the Prussian historian and military theoretician Carl von Clausewitz, is an extension of politics by military means, aimed at making the opponent submit to one`s own will. Traditional warfare involves state actors and observes some rules regarding conflict and the treatment of the involved parties (soldiers and civilians), which distinguishes it from the more recent phenomenon of asymmetric warfare, which became a more prominent matter in the XX-th Century. Asymmetric conflicts involve both state and non-state actors and guerrilla tactics, while a certain blurring of the lines tends to occur, for example in separating combatants from civilians.

Our subject matter, that of hybrid warfare, came into focus at the end of the XX-th and beginning of XXI-st Century, and seems to be mixing traditional and asymmetric warfare tactics with a significant informational component, while making intensive use of technological developments. It is also widely accepted under different other terms, such as informational or non-contact warfare, and the most common examples of hybrid warfare are the Russian interventions in Crimea and Ukraine, as well as ISIL's campaign in Iraq. In both cases, military actions were doubled by systematic ma-nipulative messages being disseminated through new media, aiming at discrediting the opponent`s ideology and to promote the preferred narrative.

Hybrid Warfare is a greyzone conflict, a grey war or an ”activity that is coercive and aggressive in nature, but that is deliberately designed to remain below the threshold of conventional military conflict and open interstate war”, according to historian Hal Brands . The purpose of the aggressors is reaching goals without risking retaliation, penalties or restrictions, and this purpose is achieved through various tactics which are usually completed by an informational component which misleads as to their author. And a significant manner of achieving this target of staying undetected is by blurring the traditional lines between conventional and non-conventional, internal and external, legal and illegal, and, eventually, peace and war.

Although there is no unanimously agreed upon definition for hybrid threats, neither for hybrid warfare or hybrid conflict, the terms are used by all major geopolitical actors and two meanings stand out, overall: first, that of a set of techniques, used variably and according to context, by state or non-state actors, with a view to attaining specific results and exploiting perceived vulnerabilities of the opponent. Hybrid threats are long term modi operandi, generally have a connotation related to information and are aimed at making the opponent vulnerable in all areas of human life - social, political, economic, institutional, as well as, in some instances, at obtaining financial/economic profit. It is important to stress that the consequences of hybrid threats are not limited to the defense or security fields, but rather that they extend warfare beyond military and political objectives, to social and economic ones. The second meaning for hybrid threats may refer to an actor, state or non-state entity, with the means (conventional, regular / irregular, legal / illegal) and motives to influence an opponent.

Other observers have classified the meanings of the term according to their field of relevance: military, from the perspective of conventional threats associated with hybrid ones, academic, as the concept is an object of perseverant study for many researchers, and political. The political understanding of hybrid threats encompasses “spread of disinformation/misinformation, creation of strong (but incorrect or only partially correct) historical narratives, election interference, cyber-attacks, economic leverage” , which, by themselves, are not deemed to be hybrid threats, but coined as such because they are perceived as “seen as unacceptable foreign interference in sovereign states’ internal affairs and space” .

There are some characteristics of hybrid threats most ob-servers agree upon and which can set the basis for a common understanding of the term. First of all, they target democratic vulnerabilities of open societies: observance of individual rights and freedoms, particularly free and uncensored speech, make informational aggressions practically unstoppable. Ubiquitous and cheap technology, instant and free communication, free markets and unhindered competition are also major advantages of open societies which are methodically targeted to become their most exploited vulnerabilities, with seriously destabilizing effects not only on individual state actors and their domestic environment, but on the international order and government systems as well.

The European Excellence Center for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE) points out, in also trying to inch closer to an universal definition, that hybrid threats exploit the thresholds of detection and attribution. A new form of plausible deniability seems to apply in the case of aggressors, which publicly deny any wrongdoing while winking at the audience that generally knows exactly who is to blame, while authorities fail to find enough evidence of involvement. Not knowing the author of an attack or not being able to pinpoint it exactly or with a high degree of certainty diminishes the possibilities of taking actions and measures and prevents retaliation.

Also, it is important to note that hybrid threats are usually rather complex techniques, and while some of them may be easier to attribute to an aggressor, others (such as cyber-attacks) are virtually impossible to pinpoint in many cases, therefore getting all pieces of the puzzle may prove a difficult endeavor. Because of the difficulties in attributing hybrid threats, it is also difficult to size the appropriate response.

Another significant characteristic of hybrid threats is the weaponizing of technology - from social media to artificial intelligence, technological advance becomes a serious offensive instrument in the hands of entities interested to reach strategic targets.

Of particular interest for the national security establishment is the aim of most hybrid threats to influence the decision making process in a manner which would meet the aggressor’s strategic goals, albeit economic, social, military or of any other type.

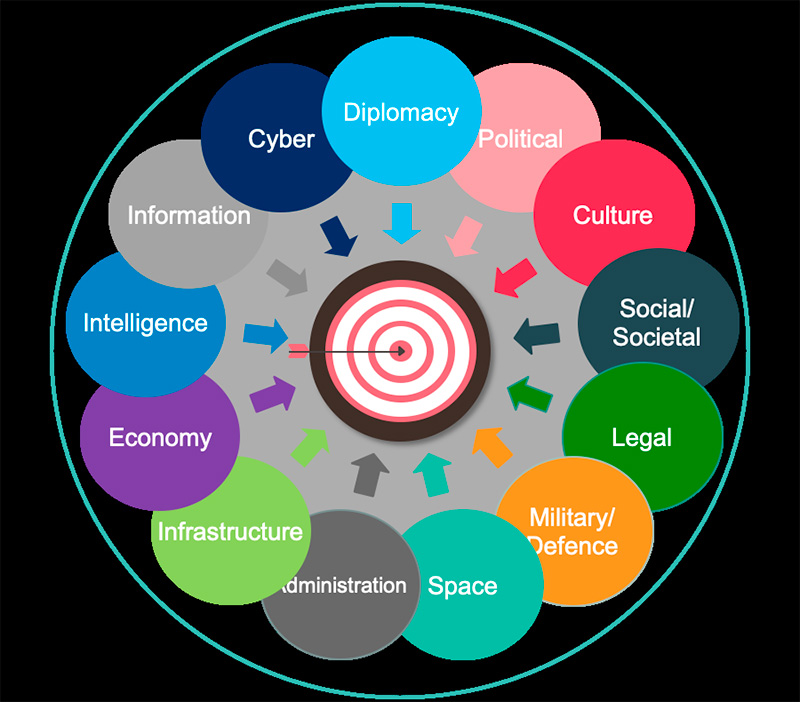

The domains in which hybrid threats can manifest and produce consequences are most areas in which states can manifest their sovereignty, and they generally affect several domains simultaneously. Available studies propose various hierarchies of targeted domains, one of the most relevant being that advanced by the European Comission with the Hybrid CoE presented in Figure 1.

Intelligence Challenges

As the previous figure reveals clearly, intelligence is one of the fields targeted by hybrid threats, and it has the legal and moral duty to act both defensively and offensively to counter such actions, through specific means and methods.

Nevertheless, intelligence is responsible for identifying and signaling attacks on most of the other targeted domains and traditionally one of decision-makers` closest allies in their endeavor to get a clear grasp of the security situation. The objective most hybrid threats make in influencing the decision-making process at various levels, including that of strategic decision-making, makes intelligence and important actor in ensuring mechanisms of decision benefit from correct and timely analysis.

Figure 1: Targeted Domains

And, pursuant to the need to have strategic decision-making free of undue interference, intelligence too is concerned with the impact hybrid threats have on democracy and social life, particularly by using cheap and accessible technology to communicate narratives with consequences such as swaying elections, seeding mistrust in the established social or political system or mobilizing and/or radicalizing protests.

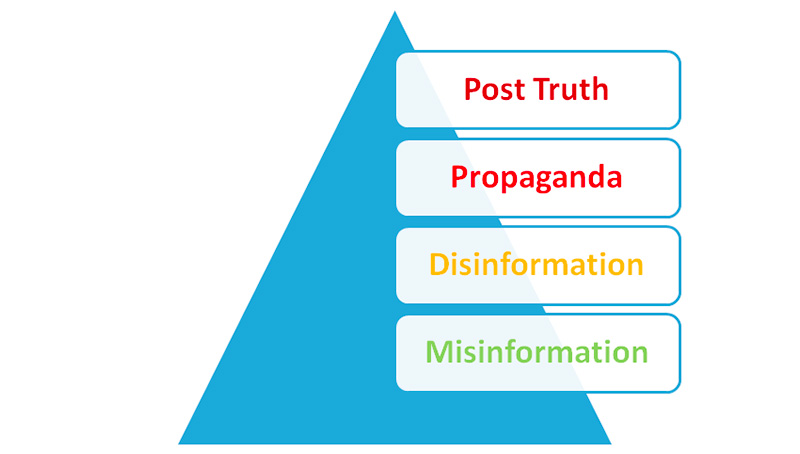

Aggressive activities with an informational component are particularly important for intelligence because information is the main working material for this particular field. Dealing with informational aggression is particularly important for intelligence, which can completely miss its core mission if left in the dark as to informational aggressions. In my opinion, those type of aggressions could be classified according to the degree of challenges they pose for democratic societies in a manner similar to that presented in the figure below:

Figure 2: Informational aggression

I wouldn`t presume to imply all of the above concepts are of concern for intelligence, but their cumulated impact is definitely a significant subject of analysis.

Beyond the informational component of hybrid threats, intelligence is also particularly interested in the manner illegal organizations are funded, in threats posed by cyber-attacks, particularly on critical infrastructures, in the establishment and activities of paramilitary organizations, as well as in the various ways in which trans-border organized crime is used, encouraged and condoned in order for aggressors to reach strategic targets.

Technological developments allow for virtually limitless possibilities to influence decision-making through various (cost-free) environments, out of which social media now seem to be the most prominent. They became a preferred news source for a majority of their users and a preferred communication environment even for decision-makers, which raises particular concerns due to the fact messages are socially engineered to reach a specific, receptive audience. Both human and machine actors are involved in promoting detrimental narratives in new media, starting from harmless misinformation to aggressive and purposeful disinformation and to strategic leaks:

Hackers are used for social engineering, gaining trust and influencing, trolls in order to post messages to deter from relevant subjects, to provoke emotional reactions, using multiple accounts, in order to artificially multiply their message.

Bots are also frequent occurrences, software apps tasked with simple, repetitive tasks or even viruses, software for indexing web pages which widely redistribute real user messages, filter comments, report legitimate messages in order to get them blocked or removed. Bots can be coordinated in BOTNETS / bot networks, which have the triple advantage of “activity, amplification, anonymity” .

Chat Bots simulate a real-live conversation with real users, combining trolls and bots to increase message-multiplication capabilities.

Private messaging apps (Whatsapp, Signal, Viber, Telegram) are a particularly sensitive environment for conveying malicious narratives, because they allow for the increased trust we all give or closed groups of friends and acquaintances. Those apps proved to be the preferred environment for specific campaigns, such as that for Brexit or the 2018 electoral campaign in Great Britain, in which an Oxford study proved particular efforts by political parties to promote their disin-formation campaigns through those media .

As mentioned before, the constant blurring of lines between military and non-military actions, legal and illegal ones, external and internal actions and particularly the difficulties to attribute such actions make it particularly difficult to establish proper regulative framework, responsible institutions to prevent and counter, difficult to educate against them.

Intelligence operates in a rather standardized manner throughout the democratic world, and most security studies analysist have identified the general framework of the intelligence activity as a cycle which starts with a planning stage for intelligence collection, a collection one, one of processing and analyzing the available data and one of disseminating the intelligence products to legal stakeholders. A brief analysis of hybrid threats` impact on intelligence can, thus, also be approached from the perspective of their impact on each of the stages of the intelligence cycle.

In the Planning stage of the intelligence cycle

Democratic intelligence agencies act on directions and priorities set by decision makers through national security and/or defense strategies, as well as through other strategic documents and decisions. There are, nevertheless, net disadvantages in having such documents as a basis for fighting the constantly shifting reality of the hybrid threats.

First, national strategies lack the flexibility required to allow for the recognition of hybrid threats, which can only be made by correlating different pieces of the puzzle, usually acknowledging only some part of the threat of attributing responsibilities to different, uncoordinated agencies, unable to piece it together.

Second, there is an issue of an inadequate timeline: security and defense strategies are, in most cases, complex documents to create, from a strictly formal perspective, but also complex documents to pass, because they generally require wide political consensus and formal approvals from qualified majorities. The process of creation is as difficult as that of approval, therefore it is no surprise they are only being updated every 4-5 years, which makes them unable to be fully correlated with versatile and constantly shifting threats. Security and defense strategies also need to be backed by solid legal instruments which can provide intelligence agencies with enough flexibility and clear responsibility to adapt and tackle such threats, but also balanced limitations to prevent slips.

Third, the relation of intelligence with decision makers is further strained, in the case of hybrid threats, by the acute need for more resources. If, for example, after 9/11 American intelligence found enough support with both decision-makers and the civil society due to the visibility and gruesomeness of the terrorist phenomenon, things are hardly the same with hybrid threats, a concept not even the academic and professional security establishment understand in similar terms, let alone politicians and civil society. And, in many cases, scarcity of budgetary allocations is doubled by the scarcity of the most precious of resources, the human one, under the pressure of the “brain drain” phenomenon countries in our region know all too well.

Internal planning and organization of intelligence activities start from national strategies, but major reorganizations and restructuring are usually necessary to allow large bureaucratic organizations to shift from managing traditional /conventional threats, to hybrid ones. Structures and activities of intelligence agencies are still, to various degrees, similar to that of the Cold War oriented towards classic threats and tributary to a high degree of compartmentalization, but this working formula can no longer provide adequate results when informational aggressions are combined with cyber-attacks, classical espionage and real military threats, for example. A new culture of cooperation needs to catch stronger roots both within and without intelligence organizations, should we expect better results in this struggle.

It is, of course, difficult for both the intelligence community and decision-makers to think outside the classical threat framework and act outside the established manner, and all this is particularly difficult when it is so difficult to accurately pinpoint the perpetrator behind insidious attack, which can make efforts seems unsuccessful, but continuous cooperation and communication among those two “tribes” is necessary in order to get optimal results.

In the Collection & Operations stage of the intelligence cycle

As already mentioned, intelligence agencies, which are essentially bureaucratic organizations, are as difficult to reshape and restructure in order to meet the new security requirements as any other organization of the type. And since their structure is still largely tributary to their previous activity, that of tackling classical threats, they are in dire need of developing tools to properly manage hybrid threats.

Some of the actual measures to reshape operations in order to be supple and flexible in approaching hybrid threats are, for example, the use of joint task forces, which involves making the actual shift from need to know to need to share. Multi-source collection is also more important than ever, in the flow of data flowing through technical, open and human sources. SIGINT and OSINT, for example, tend to focus significantly on collecting data from social media, while GEOINT benefits consistently from location data available due to telephony networks.

The pressing issue of cyberspace is also a priority in reforming intelligence in order to deal with hybrid threats. The fact that technology erases geography is actually a matter above intelligence`s “paygrade”, it is a matter to be solved by the international community at a political level, first, by means of clearer norms and regulations, and it is no secret that intelligence systems are somewhat unprepared to act accordingly, thus further pressure for organizational change, in a rather new field of assessing cyber threats.

There are also new opportunities which come at significant costs, such as cooperation with private companies or other organizations on specific fields. For example, private companies are, sometimes, more equipped to promptly identify the source of cyber-attacks, academic environments such as the Indiana University Botometer analyze social bots in a complex manner no intelligence agency would be entitled to etc. Such initiatives are helpful and they can provide useful partners in the national security enterprise, but to benefit from their experience and expertise, there is a strong need for a regulatory framework which is now completely absent. Also, any organization working on a regular basis with classified information can be more exposed to leaks and failures when working with outside partners, and needs to invest in vetting and training them.

In the Analysis/processing stage of the intelligence cycle

Needless to say that, with regards to intelligence analysis, there is also a pressing need to work in joint task forces, with a wide array of competences to make multidisciplinary analysis possible, in order to grasp hybrid threats.

But the most serious challenge to intelligence analysis is, of course, identifying truth and relevant data given the current volume of information. Identifying the “signal in the noise”, in a “cacophony of narratives”, in former security official Gregory Treverton`s words is a most daunting tasks for analysts. Big data analysis is a must for intelligence, too, but also a costly resource, while data storage and data analysis are getting more and more serious help from artificial intelligence.

Large volumes of data which need to be sorted and analyzed also increase the need to invest in superior methods of securing intelligence`s own data bases.

Finally, classic intelligence products such as national intelligence estimates may no longer be the best manner of conveying intelligence on a rapidly shifting security landscape to decision-makers which are already overwhelmed with more or less reliable information from a variety of sources. It is now the time intelligence analysis has to compete for attention and enhance its credibility, while finding more appropriate manners to provide real time, opportune and accurate intelligence.

In the dissemination stage of the intelligence cycle

The dissemination stage completes and closes the intelli-gence cycle by returning intelligence products to those who set the goals for the national security establishment, its political stakeholders. This is a much-needed point of contact between the two parties, in which intelligence needs to calibrate its products in order to meet the needs and expectations with the purpose to support informed decision-making. As mentioned, there is a need to improve intelligence products and the overall interaction with stakeholders.

Time is of the essence with intelligence dissemination. The new intelligence products need to inform in real time, so they rely heavily in IT&C; in turn, this purports new security risks and the need to ensure encryption and securization of communications. Also, intelligence products need to become more and more interactive, they are not a unilateral communication, but rather require constant feedback for further calibration.

It is also becoming increasingly difficult to inform decision-makers, due to the complexity of threats and their narrow specialization and interests. And, while attribution of hybrid threats is difficult, uncertain, takes time (as is the case, for example, with cyber-attacks) and sometimes perpetrators are obscure and difficult to connect to the mastermind / in an overall complex operation, it is difficult to keep the attention span of stakeholders and explain to them complex phenomena.

Our super-technologized world, in which information flows rapidly, also has a significant impact on intelligences` relations with policy makers. Acute competition for attention of the policy-maker with various contradicting sources is an issue. This also leads to a competition for credibility of the intelligence product: “trending narratives” may understandably be easier to perceive and understand than actual trends. On the other side of the technology coin, intelligence activity is heavily affected in its most precious quality, credibility (with stakeholders, civil society, partners), due to leaks which spread rapidly, integrated in offensive narratives, and turned into weapons.

Thus, it falls to intelligence to also try to educate its stakeholders.

On Russia. Brief Considerations

As mentioned above, one of the school-cases of hybrid warfare was Russia`s invasion of Crimea, therefore a brief mention of this revisionist regional power`s tactics would not be outside the scope of the current paper.

What Russia seeks in challenging the regional and global order is strategic and economic advantage, but without risking retaliation. It uses ”deliberate ambiguity” as a tactic in decision-making, as a strategic tool, as well as ”implausible deniability” , or open secrecy – claims one is not the author of a specific attack, despite what everybody knows (but has difficulties in proving). Such example is 2008`s attack on Serghei Skripal with a nerve agent, in which Russia constantly denied involvment.

What Russia also seeks is not necessarily to gain territorial advantages, but rather to sow disagreement and weaken consensus among allies at its immediate borders, such as NATO and the EU, while cultivating its own ambitions of regional power.

Russia`s propaganda and influence operations are by no means now, but rather have surpassed the classic concepts by adding a social-media innovation. The new tactics were practiced in Georgia and fully used in Ukraine. The most frequent Russian narratives are:

- Extremist national values, patriotism

- Superiority of the orthodox / pan-Slavic values

- Russia as a peace-seeking power

- The colonizing West

The means through which those preferred narratives are promoted are mostly those provided by new media, and can be categorized into:

- White Active Measures, consisting of direct interventions through channels openly attributed to Russia (such as Sputnik, or Russia Today);

- Grey Active Measures consist of using “useful idiots”, real users or bots, news aggregators, conspiracy theory sites (infowars.com, zerohedge.com), data dump sites (Wikileaks, DCLeaks) to willingly promote the official narrative;

- Black Active Measures mean using agents of influence, fakes (also using trolls, bots, chatbots, hackers), even trans-border crime, which provide dissociation from the perpetrator, at minimal costs.

But there is also an economic component to Russia`s struggle for influence, for which it labors through commercial transactions, acquisition of properties, strategic investments and the expansion of Russian corporations. Most of those activities can be fully legal or assume some resemblance of legality, but in many cases they also come with hidden surprises such as corruption, distortions of markets and competition through corrupt practices, attempts to compromise in-stitutions which fight corruption etc.

Conclusions

It is difficult to draw conclusions regarding hybrid threats, starting from the consistent divergences i understanding the term. Nevertheless, it is important to say that transnational organizations – to which we are members and allies - have developped tools to prevent and counter them.

With regard to the EU, Russia's invasion of Crimea of 2014 was, as mentioned, the wake-up call. The main directions for action were aimed at enhancing the legal framework, building a framework for strategic cooperation, raising awareness & education, developing analysis & monitoring tools, enhancing communication on the matter, with the overall purpose of increasing resilience.

The EU is building common digital policies, as well as a Network of Cyber security Competence Centers, led by the European Cyber security Competence Center hosted in Bucharest.

Hybrid Threats are also dealt with, at the EU level, by decision-makers responsible for the Common Foreign and Security Policy and of the Common Security and Defense Policy. The EU Strat COM division within the External Action Service has established task forces on the East, South, Western Balkans, with the purpose of countering disinformation in the respective areas

The EU INTCEN, responsible for monitoring and intelli-gence exchange, has a Hybrid Fusion Cell starting from 2016, and the EU Hybrid Playbook lays down the steps for coordinated response in case of a hybrid attack. Joint exercises and increased efforts for public communication on the issue complete the outlook on EU efforts to counter hybrid threats, with significant projects such as euvsdisinfo.eu, Media Literacy for All, European Audiovisual Observatory with regards to the latter.

The 2020 5-years EU Security Union Strategy also advances an EU approach to hybrid threats, considering their unprecedented spread and integrating the external and internal dimension, while also highlighting the importance of close NATO and G7 cooperation. There is, nonetheless, the issue of security as a first and foremost national field of interest and responsibility, therefore the Strategy does not omit to mention that countering hybrid threats is first of all a responsibility of Member States.

EU and NATO were also prompted to act together in a more coordinated fashion in order to diminish risks, and they did so by signing the joint declarations of 2016 and 2018 which further security cooperation, including on the matters of hybrid and cyber threats. In this coordinated manner, each organization is capable to contribute with its best features – NATO with the military expertise, and the EU with its experience in crisis management, in order to deter opponents and prevent attacks. In this regard, the two organizations are con-tinuously developing joint playbooks and operational protocols to better coordinate their response.

In 2017, NATO and EU both supported the establishment of the independent Hybrid Center of Excellence, which does much for communication and structured research of the phenomenon.

NATO`s 2015 Strategy on countering hybrid threats (2015) undertakes assistance of the allies under Art. 5, promising collective defense for those cases. The Joint Intelligence and Security Division has a hybrid analysis branch, and exercises with hybrid scenarios are also frequent.

As of 2018, NATO implemented the concept of Counter Hybrid Support Teams, formed of civilian experts and ready to help any ally in case of emergency. The first team of the kind was deployed in Montenegro, in 2019.

There is also a significant component of public diplomacy and NATO sets to help allies in countering disinformation campaigns through its Public Diplomacy Division and Information Offices

And since steps are taken at international level, at the na-tional one, we all need to do more and to establish more concrete measures to prevent and counter hybrid threats. In this regards, the starting point must be the permanent challenge hybrid threats pose to democratic.

As sovereign nations responsible for our own security, we must enforce reforms to enhance capabilities of detecting and reacting to hybrid threats. Intelligence as well as all other involved institutions must become less conservative, flexible and able to adjust to non-traditional attacks.

For itself, the intelligence community needs to convince decision-makers to change and adapt the legal and regulatory framework, in order to set clear priorities, directions and limitations in acting. But it is also important to stress that, given the transnational character of threats and the irrelevance of physical frontiers when face with hybrid threats, approaching intelligence as a, exclusively national responsibility does not provide sufficient instruments to address them. Hybrid threats reshape intelligence and the national security architecture.

Citate:

APA 6th Edition

Coldea, F. (2022). Intelligence challenges in countering hybrid threats. National security and the future, 23 (1), 49-66. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.1.2

MLA 8th Edition

Coldea, Florian. "Intelligence challenges in countering hybrid threats." National security and the future, vol. 23, br. 1, 2022, str. 49-66. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.1.2 Citirano DD.MM.YYYY.

Chicago 17th Edition

Coldea, Florian. "Intelligence challenges in countering hybrid threats." National security and the future 23, br. 1 (2022): 49-66. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.1.2

Harvard

Coldea, F. (2022). 'Intelligence challenges in countering hybrid threats', National security and the future, 23(1), str. 49-66. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.1.2

Vancouver

Coldea F. Intelligence challenges in countering hybrid threats. National security and the future [Internet]. 2022 [pristupljeno DD.MM.YYYY.];23(1):49-66. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.1.2

IEEE

F. Coldea, "Intelligence challenges in countering hybrid threats", National security and the future, vol.23, br. 1, str. 49-66, 2022. [Online]. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.1.2

Literature:

1. Bradshaw, S., Howard, P. (2021). The Global Disinforma-tion Order, Computational Propaganda Research Project, Oxford Institute Study, 2018, https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/93/2019/09/CyberTroop-Report19.pdf, accessed October 2nd, 2021.

2. Cormac, R., Aldrich, R. J. (2018). Grey is the New Black, Covert Action and Implausible Deniability, International Affairs, 94 (3). 477-494.

3. Giannopoulos, G., Smith, H., Theocharidou, M. (2021) The Landscape of Hybrid Threats: A conceptual model, EUR 30585, EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

4. Mumford, A. (2020). Ambiguity in Hybrid Warfare, Hybrid CoE Strategic Analysis, 24.

5. Treverton, G. (2018). The Intelligence Challenges of Hybrid Threats. Focus on Cyber and Virtual Realm, Center for Asymmetric Threat Studies, available at https://www.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:1250560/FULLTEXT01.pdf, accessed October 30th, 2021.