DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.26.2.8

Review paper

Received: October 3, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Abstract: This research study aims to monitor and analyze how Africa's borders have been managed this process, which is one of the most important internal processes in which many disciplines of social sciences are intertwined, traditional

boundary positivist approaches have addressed their various problems by focusing on the line as the main analysis unit s borders ", where these approaches focused on limiting the phenomenon of State borders to political factors, It treated it as a mirror of neighboring States' military, economic and political forces, but post-boundary studies shifted the focus to practice as an alternative unit of analysis of the line, By examining the social and spatial functions of those lines, the borders, according to Mark Salter, are only a set of human structures, and thus derive their function and meaning from the population that occupies them.

Keywords: Borders; Africa; Positivist Approaches; Post-Positivism; Line; Practice.

Introduction

Borders are a major source of concern in Africa, and in other regions of the world, they are characterized by easy penetration, weak surveillance and protection, and frequent conflicts around them, especially in the absence of a predominant demarcation and reliance on inherited maps of colonialism. All these factors have contributed directly for decades to increase crime and instability across borders, and the boom in terrorist groups' activity, which has led many African Governments to tighten their grip on those regions in an effort to counter such violations.

African countries still view borders as rigid lines, but reality confirms the failure of this approach, especially with the growing risk of internationalizing the economy, unifying culture, raising regional identities that contribute over time and crunching economic and social conditions in the formation of separatist movements.

The post-positivism approaches that emerged and evolved during the 1980s are highlighted in a joint research context between political scientists, geopolitics, philosophers, sociologists and psychologists and then visibly featured in the contributions of Anthony Giddens' structural theory by proposing the idea of freedom of economic and political activity, In addition to the contributions of the French philosopher Michel Foucault to the use of the concepts of political discourse and its role in building space, approach ", whereby all approaches allow for more effective handling of different border problems.

On this basis, this paper attempts to address a pivotal problem based on a key question: How do African States manage the continent's borders and Borderlands in the light of the various conflicts and conflicts inherited from colonialism?

In order to answer this problem, this study assumes that there are two main models of border management in Africa, the first stems from the idea of adopting a political discourse that would transform the population in Borderlands into a first line of defence of national sovereignty. The second focuses on the economic practices of social structures at borders as alternative approaches in the management of various border problems.

Methodology

This paper is theoretically based on the comparative approach, which is widely used in political science in the study of political systems, institutions and processes across local, regional and international levels. The comparative approach in this context is based on a series of empirical statements and evidence relating to the political phenomenon s political understanding of those phenomena under study. (Stafford, 2013)

By drawing on the comparative approach in this study, we seek to monitor and analyze the various policies of African countries in addressing border management based on their subordination to the comparative process that enables us to recognize and explain the great disparity between these different policies.

The study focuses on three primary cases representing distinct subregional contexts—North Africa, West Africa, and the Horn of Africa—chosen according to the following criteria:

- Geographical and regional diversity, reflecting the heterogeneity of political and security environments.

- Institutional variation, allowing comparison between countries with strong border governance systems and those with weaker administrative capacities.

- Policy relevance, emphasizing states that have implemented significant border reforms or participated in regional initiatives on border management.

The research relies on qualitative documentary data collected from official government reports, policy documents of regional organizations (such as the African Union and ECOWAS), peer-reviewed academic literature, and analytical briefs from international institutions. This is complemented by quantitative indicators, including border-crossing statistics, security assessments, and bilateral or multilateral agreements relevant to border governance.

The comparative analysis covers the period from 2000 to 2024, which captures major transformations in African border governance—ranging from post-9/11 security shifts to the rise of irregular migration and regional integration efforts.

Each case is examined within a comparative-explanatory framework designed to identify common trends and divergent policy patterns while tracing the causal mechanisms behind them. The analysis moves beyond descriptive comparison toward interpretive comparison, seeking to uncover the political and institutional variables shaping border management across different African contexts.

Africa's borders: a history of inherited conflicts

Like many other social science concepts, the concept of frontiers has historically known many developments across decades of studies and research, however, it still generally conveys to us that sense of those fictional or real lines that divide two pieces of land from each other. (Nguendi, 2012)

It is thus a set of lines that separate distinct political, social or legal zones, making them one of the most widespread topics in the field of geopolitics, and border studies derived their initial momentum from geopolitical rivalries between European powers that coincided with rapid colonial expansion and devastating world wars during the late nineteenth century, and the beginning of the twentieth century. (Joshua, 2018)

Border disputes occur locally and internationally between communities belonging to the same geopolitical entity, as well as at the international level the border dispute arises when a state claims a plot of land in a neighbouring state because of some of the qualities it possesses. These qualities can include an important historical or cultural shrine, strategic location, or economic resources, such as an oil field or deep water port. The conflict can only arise after an actual diplomatic or military conflict. (Gbenenye, 2016, p. 118)

In this context, the African continent witnessed the beginning of border conflicts immediately after the waves of independence that ravaged the continent during the mid-century. At that time, it was agreed to accept the boundaries laid down by colonialism without any changes that would facilitate the aspirations of African societies, conflict and political instability ", which directly contributed to many of the subsequent negative effects, such as conflict and political instability, this has deepened disputes and escalated discourses about whether national borders are necessary and can contribute to the development and cohesion of the African continent. (Mulindwa, 2020, p. 600)

Border conflicts are a common feature of African politics. However, different subregions have managed these conflicts very differently. This difference is most evident between West Africa and the Horn of Africa. West Africa has experienced 10 border conflicts, none of which have turned into war. By contrast, only four border conflicts occurred in the Horn of Africa, but two resulted in war. (Kornprobst, 2002) Today there are approximately 100 active border conflicts across the continent, the most important of which can be summarized in the following table:

Table I: Border conflicts on the African continent (Oduntan, 2014)

|

§ The dispute over Ceuta and Melilla between

Morocco and Spain

§ The conflict between Egypt and the Sudan over the

Halayeb region.

|

North Africa

|

|

§ The conflict over the Elemi triangle between the

Sudan and Kenya.

§ Kenya-South Sudan border dispute

§ Lake Malawi conflict between Tanzania and Malawi

§ Conflict over the Mengino Islands between Kenya

and Uganda

§ Conflict over the Badme region between Eritrea

and Ethiopia

§ The border differences between the Sudan and

South Sudan.

|

East Africa

|

|

§ Land and maritime conflicts between Cameroon and

Nigeria

§ Territorial conflicts on the island of Mabani

between Gabon and Equatorial Guinea

§ Border dispute between Burkina Faso and Niger

§ Border dispute between Benin and Niger

|

West Africa

|

|

§ Dispute over Rukwanzi Island in Lake Albert and

other areas on the Semeleki River between Uganda and the Democratic Republic

of the Congo.

§ Conflict over large parts of the Congo river

between the Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

|

Central Africa

|

|

§ The Orange River conflict between Namibia and

South Africa.

§ Border tensions between Swaziland and South

Africa.

§ Conflict between the Democratic Republic of the

Congo and Angola.

|

South Africa

|

The prevailing view among scientists suggests that border conflicts are inevitable creations of colonial domination European imperial powers seized and divided African territory through the Berlin Conference from 1884 to 1885, and European maps that determined the borders of African countries, and this view indicates that the colonial tendency of Africa represented a kind of primitive territorial seizure, which led to the division of the continent’s geography artificially and arbitrarily into segments of strategic colonial domains, where colonialism in this context intended to fragment groups. Similar cultural differences, and the gathering of disparate cultural groups, thus forming long-term conflicts. (Okoli, 2023)

While other scientists, led by "realists," have questioned this vision. According to them, colonial intervention cannot fully explain the nature and dynamics of Africa's current border conflicts, they believe states are struggling for land to gain a material advantage. Conflict is largely about ownership, access or control over natural resources such as oil and water, this means that most of today's border conflicts are driven by States' pursuit of material gains along their common borders. (Okoli, 2023)

Securitization of borders in Africa: buffer lines:

Borders provide an ideal symbolic, powerful tool to separate "us" and "for us" from "them" and "for them". In fact, the concept of national security and the state's ability to use force to defend its interests and preserve borders is often concentrated. Therefore, traditional views on national security have given a number of roles at borders and border territories and include acting as sites for assessing neighbouring States' strengths, weaknesses and intentions, as well as the provision of working areas that protect the State's essence in the event of any threat. (Diener, 2012, p. 64)

The basic and historical idea of borders is to separate different political units (States). In addition, borders aim to be a tool for controlling the flow of goods, ideas and even ideologies, It requires a range of different tools, the justification of which derives from the idea of total sovereignty over its territory, and its success in survival and continuity, where the concept of security boundaries in this context highlights the notion of a security problem and the concept of deterrence, and the idea of national defence against foreign powers, all these traditional realistic ideas directly emphasize the meaning of the sovereign State's self-reliance. Consequently, the concept of security boundaries includes the element of violence and nation-building. (Laitinen, 2001)

According to the traditional approach, one of the main tasks of security in the border area is to maximize control over any cross-border flows and movements. In this context, Carl Deutsch introduced the concept of the security of regional communities, considering that the intensity of cross-border interactions are indicators of the intensity of integration processes, which are seen as a threat to the community's identity. Thus, borders are a means of stopping the infiltration of undesirable persons, goods and information into the country. (Bentaleb, 2022, p. 1387)

Accordingly, the Copenhagen School of Monetary Studies for Security formulated its perception of border Securitization within the framework of border control and management and its scheduling as a matter of national security. This includes the use of various measures, including exceptional ones such as security and military barriers, surveillance technologies and the implementation of immigration laws to regulate the movement of persons and goods across national borders, the Securitization in this case often depends on raising concerns about terrorism, illegal migration and cross-border crime by adopting a special political discourse that portrays border security as a critical issue for the protection, safety and sovereignty of the State.

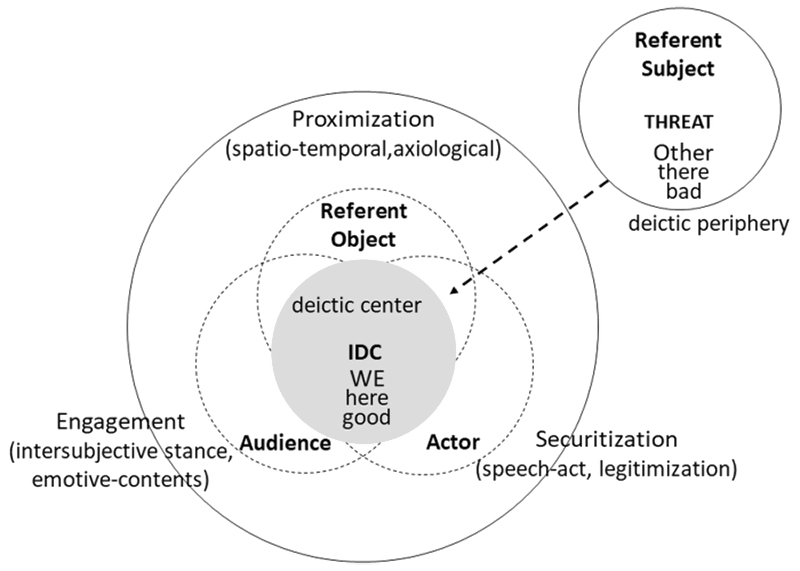

Figure 1: The Proximization Model of Securitization Discourse (Hu, 2024)

The Securitization works in this context by relying on the mechanism whereby ordinary cases are transformed into security issues. In this context, Oli Weaver provided a constructive view on security when he pointed out that the security problem is an issue so framed by political elites in order to legitimize exceptional means to resolve it. Relying on Austin, Weaver considers security to be an act of speech, arguing alongside Austin to say; Speeches may have a strong performance ability to reflect reality (Moffette, 2010)

By using them to promote an existential risk aimed at the State's and society's core policy, rhetorical practices allow for the establishment of public opinion and the public to tolerate violations that may be caused by the Securitization process. (Barry, 1998, p. 25)

The power of verbal acts (used to build security threats) can be illustrated by elite and public rhetorical practices linking Borderlands, for example, to crime, drugs and terrorism rather than focusing on poverty, lack of development and human security that support or explain the daily struggle of the population of those areas.

In fact, border management has gained recognition as a means of preventing or combating the spread of terrorism and transnational organized crime since 11 September 2001, when Al-Qaida's terrorist attacks in the United States sparked a major shift in border management frameworks around the world. Border security has continued to assume renewed importance as a safeguard against growing cross-border security threats in different parts of the world. (Ogbonna C.N, 2023)

In this context, borders have become a major source of conflict in Africa over the years. Porous borders are common on the continent, leading to cross-border crime and instability, with a high level of porosity making countries more porous by smugglers. This requires preventive measures to combat any activity that could endanger life and property or call into question the State's safety. (WN, 2018 )

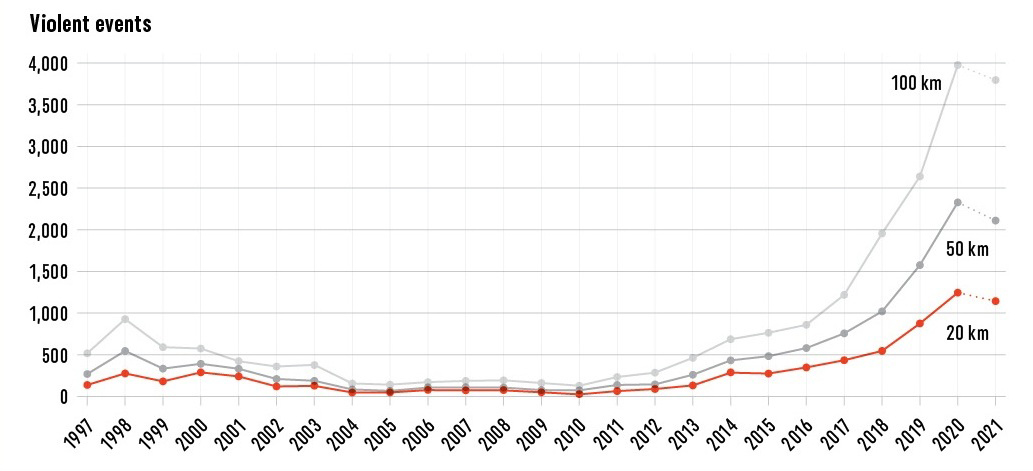

In a published study, Radell et al. examined the relationship between politically motivated violence and border lands across North and West Africa since the late 1990s in which the analysis of more than 32,500 cases of violence indicates that Borderlands are disproportionately violent compared to other areas, With some exceptions explained by the existence of large urban centres located far from the border, but the more you approach the border, the more violent you notice events, and the study also indicates that the overall relationship between political violence and border territories has changed over time. While much border-related violence was concentrated along the Gulf of Guinea until the early 2000s s borders ", the Borderlands of the Sahel region have become significantly more violent than any other region in recent decades. (Walther, 2022).

Figure 2: Violent events by border distance in North and West Africa, 1997-2021

(Africa Defense Forum, 2024)

Figure (2) illustrates the evolution of violent events occurring near African borders between 1997 and 2021, based on three spatial buffers: 20 km, 50 km, and 100 km from the borders. The data reveal a relatively low and stable level of violence from 1997 to around 2010, followed by a gradual increase starting in 2011. From 2015 onward, the number of violent incidents rose sharply across all buffer zones, with the steepest increase observed within the 100 km range, peaking in 2020 at nearly 4,000 recorded events. Even within 20 km of the borders, the number of incidents more than doubled compared to the early 2000s. This upward trend highlights the growing instability of African border regions and reflects the transnational nature of contemporary armed conflicts on the continent.

The continued violence observed in Borderlands is a regrettable reminder that State parties remain key spatial sites in the struggle to preserve sovereignty and prevent the circulation of funds, persons and weapons across national borders fuelling the conflict. (Walther, 2022)

Africa's Borderlands can be seen as areas where the historical and contemporary forms of non-governmental networks and their policies remain largely unregulated and beyond State authority. Borderlands thus become a power vacuum where a wide range of actors, both governmental and non-governmental, compete for power and legitimacy. (Gaechter, 2019)

From this standpoint, political actors on the African continent have adopted the discourse of securitization in order to invoke the exceptional situation that allows them to exercise power in the Borderlands without any humanitarian restrictions or laws that hinder the extension of their control, so that these areas turn into spaces and spaces for the exercise of brutal authoritarianism.

In Nigeria, for instance, the administration led by President Bukhari and other political actors has repeatedly classified foreigners in most of the security challenges to the country's territorial integrity. On several occasions, Governor Samuel Ortom of Beno State has called on foreign herders to launch several coordinated attacks against stable farmers and host communities in the state. Thus, it is not surprising that there are many studies linking irregular or illegal migration to Nigeria's growing national security threats. (Walther, 2022)

This situation can be explained by the competitive threat theory the competitive threat, where Securitization depends on this theory to prepare public opinion and the public for tolerance of violations it may cause. Regardless of the fact or perception of a competitive threat, it can also be understood in general terms as a multidimensional concept referring to a set of "fears" arising from a "real-life threat" resulting from perceived competition for power, material resources and well-being, or a "symbolic threat" resulting from growing concerns about the group's cultural, religious and/or normative beliefs. (Pieter-Paul Verhaeghe, 2022)

Apart from the speeches of political leaders, other sources of securitization also include media screens (images representing security threats such as bombings carried out by terrorist groups); visual representation of security threats (through dress, symbols and artefacts); Classification of travelers by nationality for passport checks; Standardize safe responses through recommended mandatory security measures. (Seda, 2015)

In fact, although it is clear why political actions try to hide behind them in justifying the security of border management, mainly organized crime and terrorism, there are many other hidden reasons that Copenhagen School of Security theorists call the hidden agenda. (Derradji, 2022)

The Securitization is linked ontologically to societal security, and societal security is closely linked to political security, but it nevertheless differs from it. While political security is linked to the organizational stability of states, systems of governance, and ideologies that grant governments legitimacy, societal security is linked to the identity and self-perception of communities and individuals who define themselves as members in the community. (Barry, 1998, p. 119)

Identity is therefore a major reason why politics of Securitization policies are embraced, as historical experience proves the involvement of the exploitation of culture as a tool for the security of many issues, which has become familiar in cultural interpretations of international relations. (Madouni, 2021)

In a similar vein, Securitization discourse has gone beyond political action, elites and the media in Africa, and has been highly sought after even among the people and the population of the Borderlands themselves. For example, the Ghanaians and the Ivorians do not simply deal with the dividing line left by colonialism, on which they found themselves, but with it based on differences in historical experience and in-depth personal identity over time, and are passed on to subsequent generations. (Scorgie-Porter, 2015)

In general, this approach is met with strong opposition in human rights circles, as many jurists, especially African ones, argue that the increasing approach to securitization will inevitably lead to the militarization of Borderlands, the violation of human rights and the marginalization of vulnerable populations, such as refugees and asylum seekers. They also point out that the securitization of borders may not effectively address the root causes of border challenges, but will undoubtedly contribute to undermining justice and reinforcing social injustice.

Social practices and border anthropology in Africa

In recent years, this anthropological interest in spatial social differentiation has led to the emergence of a strong ethnography of violent social relations that inform and combine borders. Notable examples include Jason de Leon (2015) Open Cemetery Ground, Eva Gusionites (2018) threshold. However, taking the mutual status of the Centre and the parties seriously requires anthropological attention to the integrated role of borders in shaping the urban capitalist nucleus. In other words, spatial social logic and violent border practices are essentially dominant political systems. (Campbell, 2022)

In fact, borders are not only lines on the margins of nation-states, but also political institutions and spaces made up of social and political processes. (Moyo, 2019), Anthropological theories and methods enable ethnographers to focus on communities at international borders in order to study the physical and symbolic processes of culture. This focus on everyday life, and on cultural structures that give meaning to boundaries between societies and between nations, is often absent in the broader perspectives of other social sciences. Frontier anthropology is one of the views in political anthropology that reminds sociologists outside of specialization, and some within it, that nations, States, and their institutions consist of people who cannot or should not be reduced to images created by the State, the media or any other groups wishing to represent them. (Wilson, 1998, p. 04)

The anthropological study of the daily life of border communities is at the same time the study of the daily life of the State whose agents there must play an active role in the implementation of policy and the interference of State structures in the lives of its people. When ethnographers study border peoples, they do so with the intention of recounting the experiences of people who are often comfortable with the idea that they are culturally connected to many other people in neighboring countries. The anthropology of borders simultaneously explores the cultural permeability of borders, the potential for border peoples to adapt in their ideological attempts to build political divisions, and the hardening of some nations in their efforts to control cultural areas beyond their borders. Anthropologists thus study the social and economic forces that require the creation and crossing of a variety of political and cultural boundaries in the daily lives of border dwellers. (Wilson, 1998, p. 04)

Border anthropology has realized that the places and spaces of border life rarely end at the borderline, except under conditions of severe geopolitical constraints. Ethnographic studies have consistently studied how people on both sides of the borderline not only relate to each other, but also to other distant people within their own countries. Nevertheless, not all border residents have equal power and reach ties, and all are subject, at least in part, to national discourse on differences across international borders. Thus, for many historical and contemporary reasons alike, the links between peoples within and between borders may be many or few, strong or weak, growing or diminishing, old or new, legal or illegal, peaceful or conflicting. However, such ties, and their associated relationships, are often obscured by larger accounts of national history and state projections, which focus on national integration, homogeneity within national borders, and disagreement with those across borders. (Wilson, 2024, p. 10)

However, this national discourse may be confronted with peoples' historical practices, where the movement between the present borders for centuries has been a major feature of life in Africa. People have worked to raise animals as part of livelihoods, moving across the region through much of history. They crossed borders for work, maintaining relationships and looking for opportunities, to understand the role of mobility in the lives and development of the population of the Borderlands, we need to reconsider a wide range of factors that interact in complex ways. For example, the population of the Borderlands of Africa shares the lineage, many African tribes live on the border between two or more countries. This is the same as these tribes have shared the same customs and traditions, and the conditions of colonialism have been shared for many years.

In fact, the nation-state in Africa consistently sees borderlands as marginal spaces, and the urban bias has always been present. African capitals tend to look with disdain at these regions, and consider them poor, weak, dependent, backward, regional, and deprived regions. (Scorgie-Porter, 2015, p. 288)

In many of Africa's border regions, it can often seem as if the state is absent, with the formal presence of the state, both at an administrative and visible level as well, being patchy at best. Of course, this is not the case for all African country borders, as some governments make attempts to make their presence visible and physical. Alice Bellagamba and George Clot's description of the border town of Kidal in northern Mali reminds us that the presence of the state can vary in form: “In Kidal, the state may be weak or even absent insofar as it guarantees services and economic rights to its citizens,” but it is dramatically present with its military and coercive apparatus, consisting of soldiers, trucks and weapons. (Scorgie-Porter, 2015, p. 289)

On the contrary, according to Etienne Balibar, " Borderlands are not marginal in the composition of the public sphere but are the centre in itself". (Wilson, 2024, p. 08) They do not need manifestations of militarization, or rhetoric of Securitization to secure them from threats, but it needs the developmental approach that puts it at the heart of the center, and this asserts the importance of these Borderlands in building national security strategies, on this basis, political actions in African States to ensure their security are required primarily by the shift in the management of their countries' borders and Borderlands from a security outlook based on threats coming from behind lines (securing) the economic and social outlook built on pre-line development (developmental approach), thereby ensuring that Borderlands are transformed from rigid lines into daily socio-economic and cultural practices.

The most important cornerstone of this trend today is the historical experience in the border regions of Europe, North America and other parts of the world, when the existing system of international relations is able to prevent the outbreak of global conflict after cross-border relations have become a system of interaction between actors of different sizes (from the Government and the regional political and economic elite, to the population of the Borderlands) in a process whereby integrated areas are established beyond States' borders. As a result, the research's focus shifted from conflict to the development of commercial and administrative interests. (Alexander A. Zyikov, 2015, p. 118)

African countries have all the elements for the success of this trend, as what links the residents of the Borderlands between the two sides of the lines is more than what separates them. Shared customs and traditions - as we saw previously - in addition to the promising economic and trade cooperation opportunities, especially in areas geographically distant from the centers of countries, are all factors. It contributes effectively to the development of Borderlands through social, economic and cultural practices.

Globalization and sovereignty under Africa's invisible borders

The basic idea from which the vision of invisible borders in Africa stems is that third approach that does not recognize lines, nor social and economic practices as the main units of analysis for border management on the African continent. Rather, it is the orientation that does not fundamentally believe in the idea of borders, from where the proponents of this proposal derive their ideas. Their ideology is based on the idea of cosmopolitanism, for which globalization paved the way.

Globalization has created new dilemmas for the world's sovereign States. While globalization lacks a consistent definition, a wide stream of political scientists tend to view it as increasing "international interdependence". This poses a new challenge to the traditional concept of sovereignty that underpins the state system. According to legal theorists, sovereignty is one of the fundamental characteristics of the modern nation-State. (Gerard, 2014, p. 29)

Furthermore, the occupation of territory, as Banerjee wrote, is "fundamental to sovereignty." Wachspress defines sovereignty as "an organ of frontiers or material framing that makes the sovereign responsible for the spatial integrity of the State, and extends sovereignty to a wide range with the scope of its laws and this builds a global system." More importantly, this material and legal authority requires the ability to include and exclude persons, taking into account the minimum international legal obligations, of which refugee protection is one. The material and legal nature of sovereignty has been affected by globalization, as the territorial State has shifted towards a sovereignty based on populations and modalities of governance, and views differ on how such a transformation might occur. Many researchers have therefore analyzed friction at the intersection of globalization and sovereignty and its impact on borders. (Gerard, 2014, p. 29)

The idea of invisible boundaries focuses on the perception of cyberspace through different conceptual approaches. The idea of flow space, formulated by sociologist Manuel Castles, is widely popular among geographers. The idea has been particularly popular with Internet scientists. There remains a widespread myth that cyberspace has no place, that is, it is free of constraints in the non-virtual world, which leads to the emergence of concepts such as distance death, the flat world and the end of geography. (Alexander C. Diener, 2023)

In the same context, digital sovereignty increasingly controls intellectual debates in international cyber government discourses, and is particularly interpreted as a major concern for African Governments. The borderless nature of the Internet presents challenges for many African States that have become accustomed to controlling all activities in their territories, and as such, there is an ongoing renewal of the region's digital sovereignty narrative. African Governments usually restrict citizens' access to the Internet, and there is clearly a misunderstanding of the e-governance agenda. (Ifeanyi-Ajufo, 2023)

United Nations standards of responsible State conduct in cyberspace call on States to respect the resolutions of the Human Rights Council and the General Assembly of the United Nations to promote and protect the enjoyment of human rights on the Internet. United Nations experts and high-level officials, including the Secretary-General of the United Nations, have solemnly stressed that: "Mass Internet closures, public blocking and liquidation of services by United Nations human rights mechanisms are seen as flagrant violations of international human rights law." However, African states' understanding of human rights and security, coupled with the pervasive political instability in the region, often clashes with the realities and expectations of international human rights frameworks, the balance towards Internet control is always seen as a measure of cyber security, national security and the restoration of digital sovereignty by these African nations. (Ifeanyi-Ajufo, 2023)

However, in parallels with control. A wide range of literature has come to understand how information technologies change power relationships and border-related spaces. If, for example, borders are an effective means of determining the rule of law, this idea applies to Internet law, also known as cyber laws, one of the most recent areas of legal study and litigation in which the Internet plays a central role. (Alexander C. Diener, 2023)

In Africa, the main problem of cyber law is the lack of capacity, experience and skills in the cyber legislation process, as many African countries still do not have cyber security legislation or a cyber-security strategy, as research shows that only seventeen countries out of all African countries have a national strategy. According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), only twenty-nine of the African countries have issued cyber-security legislation. (Ifeanyi-Ajufo, 2023)

The power of biometric techniques works greatly in shaping cross-border interaction in the 21st century. Governments plan to continue pumping massive sums of money into these markets, as expanding the implementation of biometric identification techniques is among the most important strategic objectives of many border security agencies around the world, from the United States to the European Union, to Thailand. to Nigeria. Biometrics effectively integrate boundaries into objects, so that people carry them without pretending as they move through space. People's identities are routinely checked before they reach national borders, and huge amounts of data about their daily lives are collected surreptitiously by border enforcement agencies and automatically stored in huge databases that people can access. One of the main effects of applying automatic biometric identification systems was to reduce national border visibility to the point of invisibility. (Alexander C. Diener, 2023)

In this context, the biometrics market in Africa and the Middle East is expected to grow at an annual rate of 21%, and the global biometrics industry is expected to reach US $82 billion by 2027, according to the United States Biometrics - Global Market Path and Analysis Report 2020. (Toesland, 2021)

The relationship between globalization and sovereignty in the context of invisible borders in Africa reveals a profound transformation in the nature and practice of state authority. Globalization has rendered borders increasingly flexible and multidimensional, shifting them from geographic demarcations to digital, economic, and biometric spaces. This evolution has eroded the visibility of physical borders without eliminating the mechanisms of control and surveillance. Sovereignty, in turn, has not disappeared but has been redistributed among a diverse set of actors — including technological corporations, financial institutions, and security networks — giving rise to new forms of hybrid sovereignty and networked borders. Africa exemplifies these dynamics, as its states navigate the dual challenge of managing global integration while preserving national autonomy. Ultimately, globalization has not erased Africa’s borders but has made them more invisible and complex, compelling African states to pursue digital and developmental sovereignty to reclaim agency over the emerging domains of power, knowledge, and data.

Conclusion

African states approach border and borderland management in ways that reflect their specific historical trajectories, socio-political contexts, and inherited territorial configurations. The enduring legacy of colonial boundary-making continues to shape governance challenges and trigger recurrent disputes, prompting many countries to adopt securitized models centered on military deployment, surveillance, and defensive infrastructure. While such measures have contributed to short-term stabilization, they remain insufficient for addressing the structural socioeconomic and political drivers of border insecurity.

Development-oriented approaches therefore offer a more sustainable alternative to exclusive securitization. These approaches emphasize the social, cultural, and anthropological realities of borderland communities and call for reducing excessive security pressures, empowering local actors, and strengthening economic interdependence across borders. By advancing community engagement and cross-border cooperation, states can foster more resilient and less conflict-prone border regions.

Nevertheless, contemporary border governance in Africa is increasingly challenged by emerging dynamics such as cyber threats, the evolving nature of sovereignty, and the progressive “invisibility” of borders resulting from digital and virtual modes of regulation. These transformations introduce new layers of complexity and risk undermining traditional mechanisms of territorial control.

To address these multidimensional challenges and move toward more effective and future-oriented border governance, African states and regional institutions should prioritize the following strategic actions:

- Accelerate the resolution of boundary disputes through negotiation, joint commissions, and—when required—arbitration by the International Court of Justice, in order to reduce persistent tensions that impede cross-border cooperation.

- Strengthen regional integration frameworks under the African Union, Regional Economic Communities (ECOWAS, SADC, IGAD, ECCAS), and the African Border Programme, with particular emphasis on harmonized customs systems, intelligence sharing, and coordinated border management mechanisms.

- Advance Integrated Border Management (IBM) by transitioning from militarized approaches to multi-agency systems linking immigration, customs, policing, health services, and local administrations, supported by expanded digital tools such as biometrics, electronic gates, and interoperable databases.

- Promote cross-border development initiatives—including transport corridors, joint economic zones, cross-border markets, and service infrastructure—to mitigate marginalization, reduce illicit activities, and reinforce legitimate state presence.

- Institutionalize community-based border security, integrating traditional authorities, civil society actors, and local networks into early-warning and conflict-prevention systems to enhance legitimacy and public trust.

- Develop joint professional training programs for border officials across African states, focusing on human rights, counter-trafficking, environmental protection, and transnational crime to unify standards and improve operational coherence.

Ultimately, a holistic governance model—combining security, development, regional cooperation, and technological innovation—is essential for African countries seeking to manage their borders more effectively and build stable, inclusive, and economically integrated border regions.

Literature:

1. Africa Defense Forum. (2024, April). Reclaiming borders. https://adf-magazine.com/2024/04/reclaiming-borders/

2. Alexander A. Zyikov, S. V. (2015). Transborder relations. In Introduction to Border Studies. Vladivostok: Dalnauka.

3. Alexander C. Diener, J. H. (2023). invisible Borders in a Bordered World Power, Mobility, and Belonging. Oxford: Routledge Taylor & Francis.

4. Barry, B. O. (1998). Security : A New Framework for Analysis. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

5. Bentaleb, S. (2022). Border Securitization in Globalization Era Concept Renewal in Context Of Comprehensive Holistic Multi-Modal Approach. ELWAHAT Journal for Research and Studies, 15(02).

6. Campbell, S. (2022). How an Anthropology of Borders Unveils the Present's Violent Structuring Logics. Anthropological Quarterly. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2022.0036

7. Derradji, H. (2022). Managing Migration and Asylum Issues in the European Space: Among Multi-Level Governance and the Securitization Options. Social Sciences Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.47577/tssj.v35i1.7002.

8. Diener, A. C. (2012). Borders: a Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

9. Gaechter, J. (2019). Border Security at the Top of African Agendas Why has border security become so important in African states and whose interests does it serve? the SAIS Europe journal of global affairs, 22(01). Retrieved from https://www.saisjournal.eu/article/20-Border-Security-at-the-top-of-African-Agendas.cfm

10. Gbenenye, E. M. (2016). African colonial boundaries and nation-building. Inkanyiso: Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 08(02).

11. Gerard, A. (2014). The Securitization of Migration and Refugee Women. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

12. Hu, C. (2024). Modeling the audience’s perception of security in media discourse. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11, 663. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03079-1

13. Ifeanyi-Ajufo, N. (2023). Cyber governance in Africa: at the crossroads of politics, sovereignty and cooperation. Policy Design and Practice, 06(02). doi:DOI: 10.1080/25741292.2023.2199960

14. Joshua, H. (2018, 06 28). Borders and Boundaries. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199874002-0056

15. Kornprobst, M. (2002). he management of border disputes in African regional subsystems: comparing West Africa and the Horn of Africa. journal of Modern African Studies, 40(03), 369–393. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3876042.

16. Laitinen, K. (2001). Reflecting the Security Border in the Post-Cold War Context. international journal of peace studies, 06(02).

17. Madouni, A. (2021). The Cultural Invasion and Its Impact on Security Breakthroughs of the Nation. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 12(08).

18. Moffette, D. (2010). Convivencia and Securitization: Ordering and Managing Migration in Ceuta (Spain). Journal of Legal Anthropology, 01(02), 189-211.

19. Moyo, I. (2019). Christopher Changwe Nshimbi, African Borders, Conflict, Regional and Continental Integration. london: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429057014

20. Mulindwa, P. (2020). Interstate Border Conflicts and their Effects on Region-Building and Integration of the East African Community. African Journal of Governance and Development, 09(02).

21. Nguendi, F. (2012). Africa’s international borders as potential sources of conflict and future threats to peace and security. PAPER No. 233. Institute for Security Studies.

22. Ogbonna C.N, L. N. (2023). Border Governance, Migration Securitisation, and Security Challenges in Nigeria. Soc 60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-023-00855-8

23. Oduntan, G. (2015, July 14). Africa’s border disputes are set to rise – but there are ways to stop them. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/africas-border-disputes-are-set-to-rise-but-there-are-ways-to-stop-them-44264

24. Okoli, A. C. (2023). Ilemi Triangle spat: how resources fuel East Africa’s border conflicts. The Conversation, February. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/ilemi-triangle-spat-how-resources-fuel-east-africas-border-conflicts-199656

25. Pieter-Paul Verhaeghe, D. D. (2022). Rental discrimination, perceived threat and public attitudes towards immigration and refugees. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 45(07). doi:DOI:10.1080/01419870.2021.1939092

26. Scorgie-Porter, L. (2015). State borders in Africa. In Introduction to Border Studies. Vladivostok: Dalnauka.

27. Seda, F. L. (2015). Border Governance in Mozambique: The Intersection of International Border Controls, Regional Integration and Cross-border Regions. University Rotterdam: Thesis to obtain the degree of Doctor.

28. Stafford, A. (2013). Comparative Analysis Within Political Science. E-International Relations. Retrieved from https://www.e-ir.info/2013/11/14/the-value-of-comparative-analysis-within-political-science/

29. Toesland, F. (2021). African countries embracing biometrics, digital IDs. Africa Renewal. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/february-2021/african-countries-embracing-biometrics-digital-ids

30. Walther, O. (2022). Security and Trade in African Borderlands–An Introduction. Journal of Borderlands Studie, 37(02). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2022.2049350

31. Wilson, T. M. (1998). Hastings Donnan. Border identities: Nation and state at international frontiers. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

32. Wilson, T. M. (2024). Borders, Boundaries, Frontiers: Anthropological Insights. Canada: University of Toronto Press, .

33. WN. (2018 ). Addressing the need for the region's bountiful resources’ protection and cross-border system implementation in Africa. Retrieved from https://www.defenceiq.com/events-bordersecurityafrica