Transnational linkages between violent right-wing extremism, terrorism and organized crime - case of Croatia

Akrap, Gordan; Matošić, Vedran

Transnational linkages between violent right-wing extremism, terrorism and organized crime - case of Croatia // CEP: Transnational linkages between violent right- wing extremism, terrorism and organized crime

Bratislava : Trnava, 2023. str. 36-44 (predavanje, međunarodna recenzija, cjeloviti rad (in extenso), znanstveni)

CROSBI ID: 1265852

Naslov

Transnational linkages between violent right-wing extremism, terrorism and organized crime - case of Croatia

Autori

Akrap, Gordan ; Matošić, Vedran

Vrsta, podvrsta i kategorija rada

Radovi u zbornicima skupova, cjeloviti rad (in extenso), znanstveni

Izvornik

CEP: Transnational linkages between violent right- wing extremism, terrorism and organized crime / - Bratislava : Trnava, 2023, 36-44

Skup

Transnational linkages between violent right-wing extremism, terrorism and organized crime

Mjesto i datum

Online, 29.03.2023

Vrsta sudjelovanja

Predavanje

Vrsta recenzije

Međunarodna recenzija

Ključne riječi

Organised crime ; VRWE ; terrorism

Sažetak

Research on the possible connection of right-wing extremism with organized crime actors shows that there are individuals who are occasionally mentioned in this context. Also, transnationally connected criminal groups from the West Balkans commit violent crimes in Croatia, mainly murders of Serbian and Montenegrin citizens, members of opponent OC groups from Serbia and Montenegro. These murders are connected to well-known criminal groups, which indicates to a cooperation with OC in the country. The background of these murders is the fight for control over the illegal narcotics trade because Croatia is situated along an extremely important smuggling route for illicit drugs towards. Western Europe.

Izvorni jezik

Engleski

Znanstvena područja

Informacijske i komunikacijske znanosti, Sigurnosne i obrambene znanosti, Vojno-obrambene i sigurnosno-obavještajne znanosti i umijeće

Ustanove:

Sveučilište Sjever, Koprivnica

Profili:

Gordan Akrap (autor)

Gordan Akrap (autor)

ABOUT THIS STUDY

This study titled “Transnational linkages between violent right-wing extremism, terrorism and organized crime” focuses on the transnational connections and cooperations between violence-oriented right-wing extremist and organized crime actors in seven countries: Austria, Croatia, Germany, Greece, Poland, Sweden, and the United States of America. It was commissioned by the German Federal Foreign Office, Division “International Cooperation against Terrorism, Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime and Corruption,” in 2022.

CEP is grateful for the constructive support and critical feedback received throughout the process by the Federal Foreign Office. We would also like to thank the renowned external project experts engaged in the production of this study, without whom this work could not have been as comprehensive.

The positions presented in this study only reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily correspond with the positions of the German Federal Foreign Office.

About CEP

The Counter Extremism Project (CEP) is a nonprofit and non-partisan international policy organization formed to combat the growing threat from extremist ideologies.

CEP builds a more moderate and secure society by educating the public, policymakers, the private sector, and civil society actors about the threat of extremism. CEP also formulates programs to sever the financial, recruitment, and material support networks of extremist groups and their leaders. For more information about our activities please visit

counterextremism.com.

About the Authors

Lead author of the study / Germany chapter

Alexander Ritzmann is a Senior Advisor with the Counter Extremism Project (CEP) Berlin on the effective countering of extremist/terrorist actors, in particular on violence-oriented far-right extremist (transnational) networks, offline and online.

He is also advising the European Commission’s Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN), where he particularly focuses on extremist ideologies, narratives and strategic communications. Alexander received his master’s degree (Diplom) in Political Science from the Free University Berlin in 2000.

Austria chapter

Dr. Daniela Pisoiu is Senior Researcher at the Austrian Institute for International Affairs and lecturer at the Universities of Vienna and Krems. She has been researching radicalization, extremism and terrorism for more than 16 years in the areas of both right-wing extremism and Islamism and including aspects related to crime and organized crime. Among others, she has researched and written on the nexus between extremism and organized crime in Europe and Austria in particular, based on a number of data sources, including fieldwork and court files.

Anna-Maria Hirschhuber has been studying Political Science and Journalism and Communication Science at the University of Vienna since September 2020. Her main topics are international politics, gender and politics, social media and new forms of journalism. She is currently writing her bachelor thesis in political science on the topic of “reintegration and rehabilitation practices for extremist and terrorist offenders in Austria”.

Croatia chapter

Assist. Prof. Gordan Akrap, graduated at Zagreb Faculty of Electronics and Computing (1994). He received his PhD at the University of Zagreb in the field of Information and Communication sciences in 2011. He is editor-in-chief of National Security and the Future Journal, founder and president of Zagreb Security Forum and Hybrid Warfare Research Institute, and a lecturer at several universities in Croatia and abroad.

Vedran Matošić, graduated (1986) from the Faculty of Political Sciences of the University of Zagreb. He worked at the Croatian intelligence agency until his retirement (2020), where he served as deputy director for analysis for nine years. Previously he was a journalist in a daily and weekly newspapers. He is president of the St. George association and the executive editor of the National Security and Future journal.

Greece chapter

Nick Petropoulos is a veteran police officer with 26 years of service with the Greek Police. He has extensive experience in international police co-operation in criminal matters, including terrorism and organized crime. Nick holds a PhD in Criminal Justice from the City University of New York and an advanced certificate in terrorism studies from John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Eleni Fotou is a forensic psychologist with a BS in Psychology from University of Utah in 2002. For the past ten years she is studying the Criminal Profile of the domestic homicide offenders in Greece. She has presented her work on the management of perpetrators at the international level, such as e.g. at the UN (New York, 2019), the European Committee of Experts on the Horizon 2020 program (Brussels, 2020), and more.

Poland chapter

Przemysław Witkowski, Ph. D. of humanities in the field of political science. Two-time scholarship holder of the Minister of National Education and Sport (2005, 2006). Author of the books Glory to superman. Ideology and pop culture (Warsaw, 2017) and Laboratory of Violence. The political history of the Roma (Warsaw, 2020).

Assistant professor at Collegium Civitas in Warsaw. Senior Research Director at the Institute of Social Safety.

Sweden chapter

Hernan Mondani is Associate Professor (docent) in sociology and Senior Lecturer at the Department of Sociology at Umeå University, Sweden. He is also a researcher at the Institute for Futures Studies and at Stockholm University. His research is mainly concerned with social cohesion, how societies maintain it and how it is challenged.

He addresses these questions through social network models of organizing processes, particularly applied to the dynamics of criminal organizing and collaboration.

Tina Askanius is Associate Professor in media and communication studies at the School of Arts and Communication, Malmö University and affiliated researcher at the Institute for Futures Studies in Stockholm. Her research concerns the interplay between social movements and digital media and spans topics such as media practices of social justice movements, and the role of online media in the mobilization of far-right extremism and white supremacist movements including the neo-Nazi movement in Sweden.

Amir Rostami holds a PhD in sociology from Stockholm University and is an associate professor in criminology at the University of Gävle. He is also researcher at the Institute for Futures Studies and Visiting Fellow at Rutgers University, Miller Center for community protection and resilience. Rostami is also a seated member of the IACP Homeland Security Committee. He holds the rank of Police Superintendent at the Swedish Police and is serving as head of the government committee against benefit crime. His main research interest is the organizing dimensions of crime.

United States of America chapter

Joshua Fisher-Birch is a researcher and content review specialist with the Counter Extremism Project, where he focuses on the extreme right, including online communications, propaganda, and social media. He has a master’s degree from American University’s School of International Service in international affairs specializing in international security. Joshua has written about extremist content, ideology, and trends in the far and extreme right and is a frequent commentator in US and international media outlets.

CEP´s Dr. Hans-Jakob Schindler and Lara Pham have edited this report.

© 2023 Counter Extremism Project. All rights reserved. Any form of dissemination or reproduction of this document or parts thereof, unless for internal purposes, requires the prior written consent of the Counter Extremism Project.

CONTENTS

Country Chapters

This study demonstrates that several violence-oriented right-wing extremist (VRWE) individuals and groups in Europe and the U.S. engage in or maintain ties with organized crime (OC). Many of the identified cases have a transnational dimension, for example, through cross border activities like the acquisition of illegal drugs for distribution or parallel memberships in VRWE and transnational OC groups. Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, VRWE-affiliated football hooligan groups, white supremacist prison gangs and a range of other VRWE individuals and groups are part of such transnational networks which are particularly visible in Austria, Germany, Poland, Sweden and the United States.

The linkages between VRWE and OC are multifaceted and vary in intensity, ranging from mere operational contacts to supply illegal materials to a full-scale transformation of VRWE structures into OC structures that follow an RWE ideology. The most common forms of VRWE-OC linkages are:

1) Supply: OC groups provide illegal drugs and weapons to VRWE groups;

2) Recruitment: Members are being recruited respectively. Individuals move between OC and VRWE milieus or are members of both;

3) Support: OC groups and VRWE groups provide security services to each other or granted access to locations for internal and external events; and

4) Transformation: VRWE groups partially or fully transform into hybrid VRWE-OC organizations.

VRWE-OC cooperation seems to be driven by the pragmatic principle of “form follows function.” Even ideologically motivated VRWE are flexible with their “values” and cooperate, e.g., with perceived “non-white” OC actors if it serves their “higher” purpose. Not appreciating this sufficiently can lead to incomplete risk assessments.

There are significant differences in the quantity and quality of identified VRWE-OC linkages between the country chapters of this study. This could mean that such cooperations are strongly connected to national strategies, developments and opportunities. It could, however, also mean that the smaller number of VRWE-OC linkages found in some countries is the result of an absence of targeted and systematic law enforcement investigations into this phenomenon and a lack of official statistical categories that could reveal such connections.

Examples of transnational hybris VRWE-OC Groups

There is a general lack of up-to-date and in-depth analyses of the various financial strategies employed by VRWE groups and individuals in many countries. In general, a “follow the money” approach, which has been successfully deployed against organized crime and in the prevention and fight against Islamist extremism and terrorism, has not been adopted with regard to violent right-wing extremism.

To foster a better understanding of the scope and size of the challenges posed by the linkages between violent right-wing extremism and organized crime, data collection, analysis and sharing practices related to OC activities and strategies by VRWE actors outlined in this study should be improved on the international, European and on national levels. In order to operationally address the phenomenon’s national and transnational dimensions, Joint VRWE-OC Task Forces should be established on the EU level and on the national levels to better enable targeted investigations.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is ideally placed to explore transnational VRWE and OC cooperation, coordinate with (inter)national Joint VRWE-OC Task Forces, and develop recommendations for governments on how to best mitigate the risks.

The financial industry plays a crucial role in combating OC and terrorist financing by identifying and reporting cases of fraud, money laundering, and other suspicious transactions. The existing legal and administrative constraints, however, hinder targeted and systematic law enforcement investigations into VRWE-OC cooperation and disincentivize systematic internal data collection within the financial sector. Therefore, financial sector stakeholders could be engaged systematically by government authorities to identify gaps in current regulations and to develop the necessary regulatory mechanisms that would allow close cooperation with law enforcement investigations targeting VRWE financial networks beyond individual criminal behavior.

The research and analysis of this study is grounded in desk research and informal interviews with civil society organizations, law enforcement officials and policymakers and builds on previous work of CEP in respect to transnational violence-oriented extreme right-wing actors.1

For the research phase, the working definitions below were applied by the researchers.

Each country chapter includes the actual respective definitions and legal frameworks for these terms and categories.

Violence-oriented right-wing extremism (VRWE)

Far-right extremism: Individual or group activities and beliefs that are motivated or justified by narratives of unequal worth of humans based on criteria like “race” or “gender” as well as by narratives of white supremacy. Extremism in particular refers to the goal of overthrowing the existing (liberal democratic) political system.

Violence-orientation Any form of support of far-right extremist actors that supports, justifies or calls for violence to achieve far-right extremist objectives, e.g., through propaganda, incitement, finances, logistic or violence itself.

Terrorism Targeted threats or attacks for political purposes.

Organized crime (OC) Organized crime refers to continuing planned, rational financially motivated criminal acts by groups of individuals. It does not include random, unplanned, individual criminal acts.

Relevant financially motivated crimes of particular interest for this study are: money laundering, including through the purchase of real estate purchases through illicit gains; tax evasion; arms dealing; selling of illegal drugs; illegal prostitution; smuggling of contraband; and selling of counterfeit goods.

Europol´s Serious and Organised Crime Threat Assessment (SOCTA) 2021 highlights that “along with terrorism, serious and organised crime continues to constitute the most pressing internal security challenge to the EU.”2 Organized financially motivated crimes were also identified as a financial strategy of some key violence-oriented right-wing extremists (VRWE) in a CEP study on the transnational connectivity of VRWE, which was commissioned by the Federal Foreign Office of Germany in 2020.3

To investigate this issue further, the Federal Foreign Office of Germany commissioned this study to explore and analyze activities and strategies of violence-oriented right-wing extremists in Austria, Croatia, Germany, Greece, Poland, Sweden and the United States that are also engaged in financially motivated organized crime (OC), with a focus on transnational linkages.

Existing studies on the extremism/terrorism-crime nexus in recent years have focused on the Islamist extremism and terrorism, while transnational linkages between right-wing extremism/terrorism and organized crime groups remains under-researched.4 This gap in knowledge can lead to a misunderstanding of the strategies of violence-oriented right-wing extremists as well as of the risks those actors pose to potential victims and society as a whole.

Hence, this study aims at informing policymakers, government agencies, think tanks, civil society organizations and practitioners working on the prevention and countering of violent extremism or terrorism and organized crime with the goal of fostering a better understanding of the linkages between VRWE and OC.

The above mentioned Serious and Organised Crime Threat Assessment (SOCTA) states about the links between serious and organized crime and terrorism: “while organised crime seeks profit above all else, terrorists largely pursue political or ideological aims. In the EU, there is little evidence of systematic cooperation between criminals and terrorists. In addition, criminals are thought to be reluctant to cooperate with terrorists because of the attention such cooperation might attract from intelligence and law enforcement services.”5

A confidential situational analysis regarding connections between the extreme-right scene and biker groups by security and intelligence services in Germany from 2013, reportedly makes a similar assessment by stating that Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs (OMCGs) were sometimes hesitant to cooperate with (V)RWEs due to the attention they receive from law enforcement, which could negatively affect OMCGs’ (illicit) business activities such as dealing with illegal arms and drugs.6 Also, in some instances, a significant number of non-German members of OMCGs were mentioned as an issue specifically hindering (V)RWE-OMCG cooperation.

At the same time, Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer stated in 2021 that “there is a dangerous mixture of organized crime and right-wing extremism [(in Austria]. If you think about that just the investigations into drug trafficking led to us being able to take this large number of weapons and explosives out of circulation. They sell and trade drugs and use the proceeds to buy weapons and explosives to destroy and shake up the free basic social order in the long term.”7

Also, the German Federal Criminal Police’s (BKA) annual situation report for organized crime, includes a subcategory for supposed connections between OC groups and terrorism/politically motivated criminality.8 Most entries are related to Lebanese, Syrian, Afghan, Russian and Chechen groups and individuals, presumably in relation to Hezbollah, the “Islamic State” and the Taliban. In 2021, the situation report mentioned for the first time a politically motivated extreme-right group, which was active in the “organized distribution of illegal drugs,” presumably referring to the Turonen (see Germany subchapter). The report emphasizes that “it is to be assumed that this was done to finance their politically motivated activities.”9

How can these – at first glance – contractionary assessments regarding the feasibility and likelihood of VRWE-OC cooperations be explained? In 2021, Katharine Petrich, who researches the crime-terror nexus, highlighted in an article in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies that “monitoring relationships between OC and terrorism is a difficult task given the current organisation of most national anti-crime and counter-terrorism agencies (i.e. generally working independently of one another with limited intelligence sharing and operational collaboration). This bureaucratic reality is unfortunately common throughout most E.U. member-states; greater collaboration has not evolved despite the record of alliances that have been forged between OC and terrorism over the decades.”10

This governmental approach of looking at organized crime and violent extremism/terrorism as very different phenomena goes beyond law enforcement and intelligence agencies. It extends to researchers, academics and policymakers, who usually are specialized in one area or the other. Petrich continues: “Traditional security thinking is biased against crime-terror convergence because it emphasizes the difference in motivation between criminal and terrorist groups. Adherents have argued that any such relationships would be transactional and short-lived because criminal groups are interested in remaining out of the public eye, while terrorist groups are explicitly interested in drawing attention to themselves. However, this perspective misses both the potential benefits of diversified activities of violent nonstate groups, and the idea that groups can pursue a range of goals simultaneously across different levels of the organization.”11

Incentives for cooperation between VRWE and OC actors are manifold. Several government, media and think tank reports have highlighted such occasional or structural cooperation in the last 25 years. Among the benefits are significant financial gains related to dealing with illicit drugs or illegal weapons, sharing of information and experience on relevant law enforcement strategies, providing security services to each other and learning from respective (illegal) business activities, e.g., for money laundering through real estate purchases, brothels, gyms/fight clubs and restaurants.

Such linkages between VRWE and OC actors are not as risky for the involved groups or individuals as is often assumed. Usually, if an illegal activity is discovered by law enforcement, the investigative focus lies on the specific crime and on the specific individuals who can most likely be convicted. For example, VRWE individuals caught dealing with illegal drugs will most likely be only prosecuted for illegal drug related charges. Very few cases were found where VRWE groups or networks, in which the accused

or charged individuals are active, were (successfully) investigated further, leading to the sentencing of leadership figures.

As far as the supposed hesitation of VRWE to cooperate with “non-whites” is concerned, Austrian VRWE have reportedly worked with the OMCG United Tribunes, which has a particularly high number of members with immigrant backgrounds.

Another argument brought forward against the cooperation of VRWE and OC actors is related to the use and distribution of illegal drugs. There is indeed an anti-drug “straight edge” movement (i.e., no drugs/alcohol/tabaco), in particular within the VRWE combat sports scenes. As shown in different country chapters of this study, however, the use of illegal drugs for the “cause” is nothing new. In summary, based on the cases of VRWE-OC cooperation identified in this study, it has become clear that the pragmatic principle of “form follows function” applies.

Even (supposedly) ideologically motivated individuals or groups will be pragmatic with their “values” if it serves their “higher” purpose. Not appreciating this sufficiently can lead to incomplete risk assessments.

This study demonstrates that several VRWE individuals and groups in Europe and the U.S. engage in or maintain ties with organized crime. Many of the identified cases have a transnational dimension, for example, through cross border activities such as the acquisition of illegal drugs for distribution. OMCGs, VRWE-affiliated football hooligan groups, prison gangs and a range of VRWE individuals and groups are part of such transnational networks, which are particularly visible in Austria, Germany, Poland, Sweden and the United States.

As demonstrated in the various country chapters of this study, cooperation between VRWE and OMCG actors or VRWEs’ involvement in OC have occurred for decades and are manyfold. The linkages vary in intensity, ranging from mere operational contacts to supplying illegal materials to a full-scale transformation of VRWE structures into OC structures that follow an RWE ideology.

The most relevant VRWE-OC linkages found also have clear transnational dimensions. Forms of cooperation include:

• Supply: OC groups have provided illegal drugs and weapons to VRWE groups;

• Recruitment: Members are being recruited respectively. Individuals move between OC and VRWE milieus or are members of both;

• Support: OC groups and VRWE groups provided security services to each other or have granted access to locations for internal and external events; and

• Transformation: VRWE groups partially or fully transform into hybrid VRWE-OC organizations.

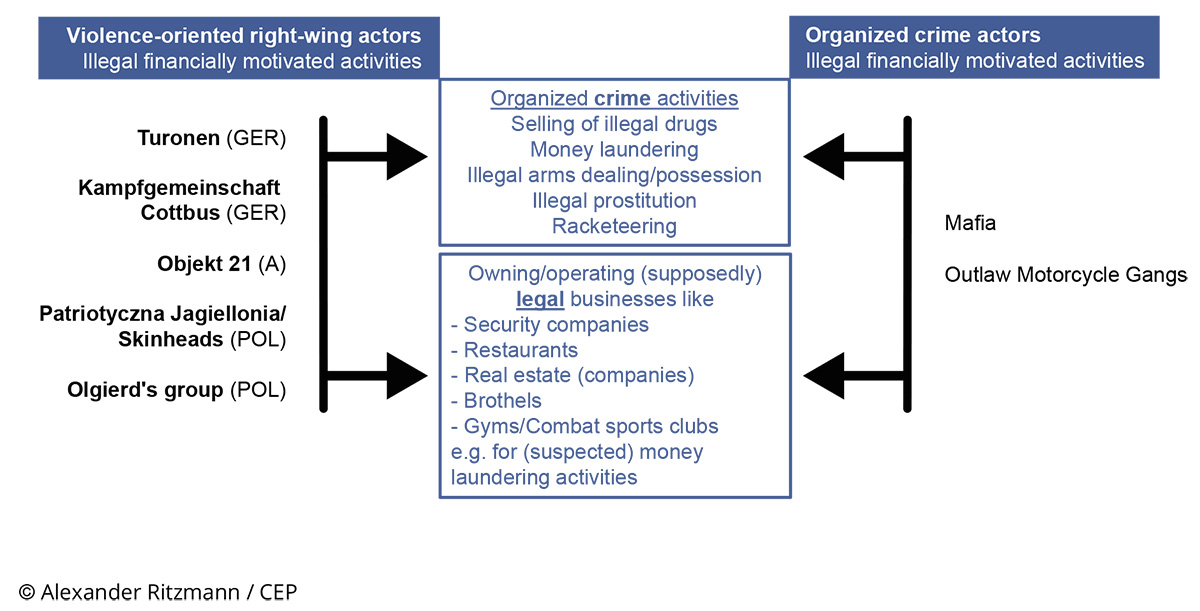

The graph shows five select transnational hybrid VRWE-OC groups and lists the illegal activities they are or were reportedly involved in.

There are significant differences in the quantity and quality of identified VRWE-OC linkages between the country chapters of this study. This could mean that such cooperations are strongly connected to national strategies, developments and opportunities. It could, however, also mean that the smaller number of VRWE-OC linkages found in some countries are a result of the absence of targeted and sys

Examples of Transnational hybrid VRWE-OC Groups

- Violence-oriented right-wing actors Organized crime actors

- Illegal financially motivated activities Illegal financially motivated activities

- Organized crime activities

- Selling of illegal drugs

- Turonen (GER) Money laundering

- Illegal arms dealing/possession

- Kampfgemeinschaft

- Illegal prostitution

- Cottbus (GER)

- Racketeering Mafia

- Objekt 21 (A) Owning/operating (supposedly) Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs

- legal businesses like Patriotyczna Jagiellonia/ - Security companies

- Skinheads (POL) - Restaurants

- - Real estate (companies)

- Olgierd's group (POL) - Brothels

- -Gyms/Combat sports clubs e.g. for (suspected) money laundering activities

© Alexander Ritzmann / CEP

tematic law enforcement investigations into this phenomenon and the lack of official statistical categories that could reveal such connections. Hence, a small number of visible cases of VRWE-OC linkages does not necessarily indicate the absence of extensive VRWE-OC cooperation in the context of a particular country.

Austrian-German-Swiss-Croatian-Western Balkan connections

Particularly strong transnational connections between VRWE groups that are also active in organized crime are visible in Germany and Austria. The Turonen from the state of Thuringia were and are currently on trial for violent crimes, selling illegal drugs, illegal and forced prostitution as well as money laundering. The prosecution estimates the total earnings of the accused Turonen members to be more than €1.2 million, generated between the fall of 2019 and February 2021. Leading members of the Turonen were active in the Thüringer Heimatschutz and open supporters of the National Socialist Underground (NSU), Germany’s deadliest RWE terrorist organization since 1945. Thuringia’s ministry of the interior assessed that Turonen do not only have networks of contacts within the extreme right-wing scene in Germany but also across the whole of Europe.

Members of a VRWE network called Objekt 21 from Upper Austria, which was officially dissolved in 2011, but some members reportedly continue to be active until today, primarily serving as the armed and violent partner of OC groups. Their members were accused of arson, burglary, violence, kidnapping, extortion, robbery, illegal arms and drugs trafficking, and illegal prostitution. The group’s leader, as well as multiple members, have since been convicted of a variety of crimes, including terrorism-related charges and for financially motivated crimes. Affiliated VRWE actors in Austria are strongly connected with the Balkan region. Objekt 21 cooperated directly with the German VRWE groups Freies Netz Süd and the Aktionsgruppe Passau. At least one member of the Turonen was also a member of Objekt 21.

The Turonen and Objekt21 have (had) clear connections to transnational OMCGs such as the Hells Angels and the Bandidos, who have long been (accused of) being involved in organized crime. For example, a member of the Bandidos Berlin City MC was reportedly supplying the Turonen with illegal drugs, in particular with four kilograms of crystal meth. Another supplier of illegal drugs for the Turonen is reportedly connected to the Armenian mafia. One individual that supported this supplier is a (supposedly former) VRWE and member of Garde 81, the support club of the OMCG Hells Angels Erfurt MC.

The Turonen are also well connected to VRWE actors in Switzerland, in particular through the transnational VRWE Blood and Honour network. The founders of Objekt 21 are also reportedly affiliated with this network.

The Turonen, Objekt 21 and Blood and Honour structures in Switzerland organized dozens of white supremacy/hate music concerts and festivals (separately and in cooperation) with up to 6,000 participants at some events and with supposedly legal profits ranging between €100,000 and €140,000 for some events. This includes white supremacy/hate music concert in the Kanton of Unterwasser in Switzerland with more than 5,000 participants. The estimated turnover there was between €200,000 and €350,000.

In Austria, at least 20 illegal weapons arsenals were discovered in the right-wing extremist scenes between 2019 and 2020. The financing of these illegal weapons and ammunition by VRWE actors in Austria was reportedly generated through proceeds from the trade in illegal drugs. It seems likely that Austrian VRWE actors have connections to VRWE-OC structures in the countries of former Yugoslavia and that at least some of the illegal weapons and ammunition seized by Austrian authorities hailed from this region.

Transnationally connected criminal groups from the Western Balkans commit violent crimes in Croatia, which is situated along an important smuggling route for illicit drugs towards Western Europe.

Polish-German connections

In the Polish cities of Białystok and Gdańsk, two VRWE groups were not only subcontracted by criminal organizations but ultimately took control of the organized crime activities. Starting in 2006 and 2009, they ran the illegal drug distribution, illegal prostitution, cigarette and alcohol smuggling, human trafficking and racketeering targeting clubs and prostitutes, and were responsible for violent assaults and murders. After a few years, they had transformed into VRWE-OC hybrid organizations. The key transnational activities of these Polish VRWE-OC groups were primarily focused on the smuggling of illegal drugs.

In Gdańsk, the organization referred to as Olgierd’s group but which purposely remained nameless to complicate prosecutions, was comprised of the OMCG Bad Company and a legal charity. The leader is a former nazi-skinhead and an active member of the VRWE transnational Blood and Honour network. In Białystok, the dominant VRWE-OC group Patriotyczna Jagiellonia, known locally as skinheads, also belonged to the transnational Blood and Honour network and have openly used the network´s brand, logos and badges, including the SS-Totenkopf (skull) symbol and swastikas. Both groups have reportedly invested in real estate and legal businesses. According to media reports, criminal cases against this group were mishandled and only lower ranking members were investigated and prosecuted after 2015. VRWE individuals and organizations (formerly) affiliated with the Inferno Cottbus 99 VRWE football hooligans network from Brandenburg, Germany, are or were reportedly active in organized crime (illegal drugs/illegal prostitution/racketeering/tax evasion). Reports also indicate that they are well connected to VRWE groups in France, Russia, and in particular with the football ultras from Beskid Andrychów and Beskid’08 in Poland. In recent years, members of Inferno Cottbus 99, which pretended to dissolve in 2017 to hinder investigations and prosecution, joined the VRWE network Kampfgemeinschaft Cottbus (Fighting Association Cottbus). This group serves as a platform for hooligans, MMA-fighters and VRWE businessmen who own private security companies, merchandise stores and restaurants and has reportedly about 115 members. In February 2020, a VRWE MMA fighter of the Kampfgemeinschaft Cottbus was shot dead in public. He was closely affiliated with the OMCG Provocateur MC Eastside, which serves as a supporter club for the Hells Angels MC Cottbus. Kampfgemeinschaft Cottbus was unsuccessfully investigated as a criminal organization by local prosecutors in 2019, but investigations and prosecutions against individual members continue until today.

White supremacy/hate music concerts and festivals in Poland, for example in Białystok and Gdańsk, as well as in in Germany, serve as motivational and strategical meeting hubs for the transnational VRWE milieu. At such events, Polish VRWE meet with VRWE-OC individuals and groups such as the above mentioned Turonen, Objekt 21 and affiliated OMCGs.

Club 28 (28 is reference to the letters B and H for Blood and Honour), plays a central role in the organization of white supremacy/hate music concerts in Poland.

It operates in the region of Lower Silesia in Poland and serves as a platform for VRWE from all over Europe, including the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Hungary, but also from the United States, Russia, Ukraine, and Estonia.

Polish VRWE reportedly have met with German VRWE like Michael Hein from Frankfurt (Oder), Marko Gottschalk from Dortmund and Tommy Frenck from Thuringia, mainly in the context of concerts. Tommy Frenck is a key VRWE figure in Germany.

He has co-organized concerts and festivals with the above mentioned German VRWE-OC hybrid group Turonen.

The pioneering nature of this study has also exposed key challenges for painting a comprehensive picture of the transnational nexus of violence-oriented right-wing extremism, terrorism and organized crime.

- Challenge: Lack of a statistical category for the VRWE-OC linkages

The seven countries at the center of this report currently do not maintain a separate category in their domestic crime statistics which reflects the existing VRWE-OC nexus.12 If a VRWE individual or group is (accused of) committing financially motivated crimes, such a case will be entered only as a financially motivated crime. Equally, if members of hybrid VRWE-OC groups or for VRWE members of organized crime organizations are (accused of) committing a violent hate crime, then this crime will only be counted in the “politically motivated/hate” crime category and will not be connected to the affiliated OC organization. This lack of aggregated statistical data regarding individuals and groups who are involved in VRWE and OC, results in gaps in the understanding the actual scope and size of the transnational VRWE-OC nexus phenomena. Cases in which such a nexus exist must be compiled based on media reports as well as the professional experience of experts, which necessarily leads to an incomplete picture.

- Challenge: Police and state prosecutors operate in “silos of focus and responsibility”

In most of the countries analyzed for this report, police and state prosecutors are structured in specialized departments, which focus either on politically motivated or on financially motivated crimes. This can lead to separated silos of focus and responsibility where highly specialized police officers and prosecutors are mandated to operate only within their area of responsibility. This administrative structure complicates and, in some cases, prevents cooperation concerning extremism/terrorism-financially motivated crime cases. Rather, one of the departments will take over the case, designating this either as extremism related or organized crime related. Accordingly, reports on cases of VRWE-OC cooperation or on hybrid actors were mostly not a result of targeted investigations by cross-department law enforcement cooperation into such a nexus.

- Challenge: A focus on single-cases, not on networks

When investigating politically motivated crimes, law enforcement generally sets a focus on prosecuting the accused individual(s). Affiliations with VRWE or OC organizations of the suspect(s) are of secondary concern, unless they are directly connected to the crime. As a result of such a single-case approach when investigating VRWE related crimes, law enforcement and prosecution may miss the opportunity to identify, expose and combat (transnational) VRWE networks and connections to organized crime organizations.

This study demonstrates that a single-case focused law enforcement approach is the standard across the researched countries when investigating politically motivated individual crimes. Only two countries (Germany and Greece) have actively investigated the VRWE-OC nexus and only one country (Germany) has recently adjusted their strategies towards a stronger network focus, although without addressing VRWE-OC connections specifically.

The larger VRWE groups and networks highlighted in this study, often also operate (supposedly) legal security businesses, restaurants, bars, merchandise stores, or organize hate music concerts or combat sports events. Some of these businesses can generate significant amounts of income with ballpark numbers in hundreds of thousands of euros in turnover. At the same time, it is a declared strategy by some VRWE to buy real estate for investment purposes, which then also serve as “fortresses in enemy territory.”13 However, these business activities are usually not in the focus of the investigation when a crime is committed by members of such networks. Given the general anti-government and anti-establishment ideology of the members of such networks, an assumption of complete legality of their (supposedly) legal business activities may miss important additional disruption opportunities.

In this context, illegal activities like tax evasion or money laundering should be a major concern for law enforcement and tax authorities. Criminal investigations with an “follow the money” approach by law enforcement or prosecutorial authorities concerning VRWE actors were not found during the research for this study.

To foster a better understanding of the scope and size of the challenges posed by the linkages between violent right-wing extremism and organized crime, data collection, analysis and information sharing practices related to the OC activities and strategies by VRWE actors outlined in this study should be improved on the international, European and on national levels. For example, analysts in anti-organized crime and counterextremism/terrorism law enforcement agencies could be trained together on how to identify existing linkages between VRWE and OC.

Regular information exchange structures and mechanisms could be established.

Improved data collection, analysis and information sharing related to OC activities and strategies by VRWE actors can also be effective mechanisms to anticipate and identify relevant future developments and trends regarding the behavior of different types of VRWE groups and their members. For example, the current Russian war of aggression against Ukraine will likely have consequences regarding the smuggling and availability of arms, ammunition and explosive materials. The return of battle hardened, trained, networked and experienced right-wing extremist foreign fighters from Ukraine to their home countries could lead to increased security challenges in the (trans)national VRWE and OC milieus.14

To operationally address the national and transnational linkages, Joint VRWE-OC Task Forces could be established on the EU and national levels to conduct targeted investigations. Such joint task forces should include law enforcement (including the departments for politically and for financially motivated crimes), prosecutors and tax authorities to better enable the identification, investigation and prosecution of VRWE-OC activities and networks (“follow the money” approach). The mandate for such task forces should in particular include prioritized and coordinated company and tax audits for VRWE-related commercial entities as well as in-depth investigation into existing VRWE-OC connections, with a focus on the VRWE key actors in each country (entrepreneurs of extremism). Uncovering undetected illegal activities will also likely lead to increased opportunities for the confiscation of financial assets, for instance, of real estate. For example, to explore and target the interface between illegal and supposedly legal activities and income streams of VRWE and financially motivated criminal actors and networks, lessons learned from the Administrative Approach,15 a methodology and toolkit developed by the European Union to fight organized crime, could be considered.

The private sector, particularly the financial industry, already plays a crucial role in combating OC and terrorist financing by identifying and reporting cases of fraud, money laundering, and other suspicious transactions. However, as many VRWE structures are not yet officially classified as terrorism related, legal and regulatory mechanisms that require private sector stakeholders to develop knowledge and tools enabling them to identify the VRWE connection of the relevant criminal activities do not yet exist. Therefore, further awareness raising within the financial industry concerning this issue is necessary. As stakeholders within the financial industry hold relevant data concerning both the ostensibly legal as well as the clearly illegal financial activities of VRWE structures, including when these cooperate with OC structures, enabling these stakeholders to identify patterns of behavior more effectively will likely also result in additional opportunities for law enforcement to disrupt these.

Such awareness raising activities could include the continuation of the special project of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) on the financing of ethnically or racially motivated terrorism financing that has already produced important results.16

Given the long-standing expertise of the organization to develop effective recommendations to hinder the misuse of the financial sector for money laundering and terrorism financing, the FATF is ideally placed to explore transnational VRWE and OC cooperation, coordinate with (inter)national Joint VRWE-OC Task Forces, and develop recommendations for governments on how to best mitigate the risks.

Finally, the existing legal and administrative constraints not only hinder targeted and systematic law enforcement investigations into VRWE-OC cooperation, they also disincentivize systematic internal data collection within the financial sector.

Therefore, financial sector stakeholders could be engaged systematically by government authorities to identify gaps in current regulations and to develop the necessary regulatory mechanisms that would allow close cooperation with law enforcement investigations targeting VRWE financial networks beyond individual criminal behavior.

Austria

Several cases demonstrate that some violence-oriented right-wing extremists (VRWE) cooperate with organized crime (OC) actors in Austria. The distribution of roles between OC and VRWE cannot be clearly distinguished, as some VRWE were found to act as enforcers for OC, yet in other cases, OC groups provide security services to VRWE. Such cooperation is often facilitated by overlapping memberships between football hooligans, right-wing extremists, martial arts groups and OC outlaw motorcycle gangs. Beyond this cooperation, VRWE also tend to engage in organized crime activities to raise funds. A recent pattern appears to be VRWE engaging in drug trafficking and using the proceeds to procure illegal weapons. Transnational connections and cooperation exist in a number of cases.

Germany

A variety of cases of violence-oriented right-wing extremist individuals or groups in Germany involved in financially motivated crimes do exist. These are particularly related to the distribution of illegal drugs, illegal prostitution, bank robberies or money laundering. Some VRWE actors in Germany cooperate with, or are part of, outlaw motorcycle gangs or VRWE affiliated football hooligan groups, which often have transnational connections. A key VRWE group with ties to VRWE actors in Austria and Switzerland morphed into a VRWE-OC hybrid organization and is currently on trial for a series of financially motivated crimes.

Poland

Relations between organized crime (OC) and violent right-wing extremists (VRWE) are very close. The most developed links between VRWE and OC milieus are in Gdańsk and Białystok. In these cities VRWE groups seemed to have largely replaced other OC structures and occupy a central position in the local criminal underworld, recruiting their “soldiers” from football hooligans and dealing primarily with prostitution, drug trafficking and extortion. VRWE/OC actors in Gdańsk, are also active in outlaw motorcycle gangs. Transnational connections do exist.

Sweden

Sweden can be described as the Nordic hub for extreme right movements in the region. There have been several cases of right-wing extremist individuals being recruited into the outlaw motorcycle milieu. Considering direct relations of criminal co-suspicion (i.e. right wing extremists committing financially motivated crimes) in the period 1995 to 2016, about one third of such links involving violent right-wing extremism occur with other milieus, amongst which the most prevalent are outlaw motorcycle gangs.

United States of America

White supremacist prison gangs are engaged in profit-motivated crimes such as illegal drug sales but are criminal enterprises first, ideology plays only a secondary role. Several outlaw motorcycle gangs, which have engaged in drug and arms trafficking, have members that hold extreme right-wing beliefs or are affiliated with violent right-wing organizations.

Greece

The primary VRWE actor in Greece was Golden Dawn, which was declared an organized crime group in 2020. Allegations that the group funded itself through mafia-style criminal activities such as money laundering, trafficking, or involvement in protection rings, could not be proven during the trial.

Croatia

Research on the possible connection of right-wing extremism with organized crime actors shows that there are individuals who are occasionally mentioned in this context. Also, transnationally connected criminal groups from the West Balkans commit violent crimes in Croatia, mainly murders of Serbian and Montenegrin citizens, members of opponent OC groups from Serbia and Montenegro. These murders are connected to well-known criminal groups, which indicates to a cooperation with OC in the country. The background of these murders is the fight for control over the illegal narcotics trade because Croatia is situated along an extremely important smuggling route for illicit drugs towards. Western Europe.

Dr. Daniela Pisoiu, Anna-Maria Hirschhuber

DEFINITIONS and HISTORY

The legal definitions for crimes related to terrorism and a number of extremism-related crimes, are as follows:

278b StGB (criminal code): A terrorist organization is a long-term association of more than two people which is designed to ensure that one or more members of this organization carry out one or more terrorist offenses (section 278c) or engage in terrorist financing (section 278d).

278c StGB defines terrorist crimes through a list of general crimes such as murder or kidnapping, accompanied with a specific motivation: if the act is likely to cause serious or long-term disruption to public life or serious damage to economic life and is committed with the intention of gravely intimidating the population, public bodies or an international organization to an act, toleration or coerce omissions or gravely upset or attempt to destroy the basic political, constitutional, economic or social structures of any state or international organization. Additional legal provisions related to terrorism are: terrorism financing (since 2018), incitement (since 2013), terrorism training (since 2011).

- 246 StGB, 247a StGB anti-state organizations (since 2016);

- Verbotsgesetz (prohibition law) – Wiederbetätigung (re-activation) in the sense of

- National Socialism (VerbotsG §§ 3a-3j)

- 283 StGB Propagation of hate against ethnic and religious groups

- 278 StGB criminal organization

- The definition of right-wing extremism used by the Directorate for State Protection and Intelligence (DSN) (until 2021 named “Office of the Protection of the Constitution and Counter-Terrorism (BVT)”) is as follows:

- “…a collective term for political views and efforts - from xenophobic/racist to National Socialist re-activation - which, in the name of the demand for a social order characterized by social inequality, reject the norms and rules of a modern democratic constitutional state and fight it with means or approval or acceptance of violence.”17

Violence-oriented right-wing extremism (VRWE) in Austria is a very diverse milieu, ranging from Neo-Nazi organizations, to a certain type of fraternities (“Burschen-schaften”), ‘subcultural’ networks, in particular groups linked to the transnational Blood and Honour network, to groups of the so-called New Right, i.e. Identitarians (and follow-up groups such as ‘The Austrians’). The latter have become more prominent in the last years as their propaganda has capitalized on the so-called ‘migration crisis’ and many of their narratives have been taken up in mainstream politics. They also cause headlines because of their extreme propaganda politics and due to their transnational network. A leader of the Identitarians was for instance linked with the Christchurch Shooter who donated a sum of 1500 Euros to him personally.18 While the group attempts to publicly state their commitment to peaceful means and reject violence, there has been a number of violent incidents by their members and supporters.19 Recently, a person convicted for preparing a terror plot was found to also have owned merchandise of the Identitarians and their successor groups,20 and was depicted in the communication of the Ministry of the Interior as member of the Identitarian Movement Austria/DO5 (DO – Die Österreicher Engl. The Austrians)21. An appraisal of the recently adapted law on forbidden symbols described the group as having a latent communication strategy that signals a readiness to use violence.22

The numbers shown in the annual reports of the Austrian Office of the Protection of the Constitution (BVT, recently restructured into Directorate for State Protection and Intelligence (DSN) don’t indicate a clear trend from 2000 until 2007.23 However, it is clear that from 2007 onwards the number of criminal complaints increased drastically.24 Following an incident where a member of the Austrian military force was caught wearing a self-made SS uniform but subsequently was allowed to keep his job25, the government announced a reform of the Prohibition Act, including expanding the jurisdiction abroad.26

In 2015 the DSN assessed that jihadi terrorism was the most severe threat to national security.27 In 2015, 1,156 acts with a right-wing extremist, xenophobic/racist, Islamophobic, anti-Semitic background were recorded, 54,1 percent more than in 2014 (750 acts). The clearance rate for these crimes rose from 59,7 to 65,1 percent in the same period.28 There were 1,691 reports, most of them (953) under the Prohibition Act. 695 charges were filed under the Criminal Code (including 282 charges of incitement to hatred and 289 of damage to property)29. In 2020 there were 1,364 reports (as compared to 1.678 in the previous year) out of which 801 under the Prohibition Act (vs. 1,037 in the previous year).30 The latest report31 of the Office of the Protection of the Constitution – newly reformed into the Directorate for State Protection and Intelligence, and covering the year 2021 does not include these criminal statistics anymore, however they have been made available otherwise and they show an increase (see below in the section on statistics). Recent reports also refrain from communicating a ranking of the violent extremist threats.

The connection between VRWE and organized crime has primarily been a characteristic of the subcultural networks of the scene, in particular the Blood and Honour network, the biker and hooligan milieu, but also the Identitarians. The latter group has been generally careful to avoid overt incitement to violence, however individual incidents have been recorded as mentioned above. Furthermore, the most recent intelligence report assesses Identitarian publications as supporting violence in political confrontations32.

The most prominent case of VRWE involvement with OC in Austria is the group “Objekt 21”, named after the address of their house being Windern 21 in Upper Austria.

Between 2010 and 2013 a number of individuals with ties to the Blood and Honour network rented an old farmhouse in that location. This group committed a number of crimes: “robberies, burglaries, assault, intimidation, extortion, kidnapping, drug and arms trafficking, attacks with incendiary devices and butyric acid in the red-light milieu.”33 The group was composed of 30 individuals and 200 sympathizers and cooperated with unnamed biker groups in Bavaria, the biker group Hells Angels MC Germany34, the “Freie Netz Süd” (FNS) in Bavaria, the Aktionsgruppe Passau35, and with Neo-Nazis in Thuringia, the so called “Turonen”.36 “Objekt 21” was also described as the armed and violent partner of OC groups and networks, mainly responsible for intimidating and attacking the rivals of these criminal networks.37

Journalists and judicial officials labelled the group’s activities as a conscious effort of establishing a ‘mafia network’.38

A further connection between VRWE and OC groups is suggested by personal overlaps in the wider circles of the Identitarians, the OC biker group United Tribuns MC, and the Sportgemeinschaft Noricum (SGN).39 A report by the Austrian civil society organization OERA highlighted multiple individuals that provided security services at public demonstrations of the Identitarians beginning in 2015, while also being members in SGN and having ties to United Tribuns MC. Noricum and United Tribuns MC are both presumed to have been involved in illegal prostitution, while also offering security services.40

KEY PLAYERS and LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Investigations of cases with both politically motivated crimes and financially motivated crimes are mostly carried out by the state criminal police and are usually initiated by investigations into actions of purely OC/criminal nature. That is, investigations of this nature do not usually start with an interest for the right-wing extremist scene. Scenarios that are typical are described in the public version of the annual DSN report from 2021: “In 2020, numerous house searches were carried out on suspicion of crimes under the Prohibition Act. Relevant material with a National Socialist background, electronic devices such as mobile phones, computers and data carriers as well as weapons, ammunition, explosives and war material were seized on a large scale from the suspects.”41 Indeed, this report does not mention any VRWE organizations or groups by name, except for the Identitarians and “Die Österreicher” (DO5) as right-wing extremist groups, and does not approach the issue of possible VRWE-OC connections at all. The latest report covering 2021 again focuses to a great extent on the Identitarians and on The Austrians, including their capitalizing on the pandemic and the respective demonstrations, also mentions Burschenschaften and continues to not mention information on connections to OC. It merely notes the possible, general trend of recruitment from violent criminal scenes42.

There is substantial overlap between the Identitarians and DO5 in terms of content and personnel.43 In general, the group membership is heterogeneous, but predominantly male. While there were multiple charges brought against the Identitarians and their members, they were acquitted from the charge that they were attempting to establish a criminal association44 and investigations related to terrorism charges against them were discontinued too in 2018 and 2021.45 The movement was investigated on the suspicion of terrorism following donations that were received from the Christchurch attacker by the leader of the Identitarians Martin Sellner. Investigations into potential fraud and embezzlement in connection with the donations were also discontinued.46 However, thirty-two individuals related to the Identitarians on the authorities’ list had been convicted of various offenses, including aggravated assault, rape, extortion, robbery and Nazi reenactment, among others.47 The group also has ties to the OC biker group United Tribuns through members and supporters that were active in both groups.48 Some of the Identitarian associations are under investigation for using funds for other purposes than the ones declared in the statutes49.

In general, the year 2020 displayed similar tendencies as the years 2015/16, that had heightened activity from the right-wing extremist milieu. In 2020, various milieus within the domestic right-wing extremist landscape (neo-Nazis, skinheads, New Right) came together and participated in various public demonstrations. However, according to the annual DSN report, this suggests only temporary associations and not long-lasting tendencies toward closer cooperation.50

Still, in 2020 a significant arsenal of weapons was found in Austria, which were determined to have been compiled for a right-wing militia in Germany. Money from drug trafficking — mainly by the sale of amphetamine, cocaine, marijuana and heroin — was used to procure weapons intended for the establishment of a “right-wing radical militia” in Germany.51 The main suspect is reported to have organized the arms deals during various phases in which he was released from prison.52 In general, several such depots have been found in Austria over the last few years – Chancellor Nehammer stated, “that enough weapons had been found to plunge the republic into a severe crisis”.53

On the “National Joint Action Day Against Hate Crime” in 2021 the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and Counterterrorism, state offices and also state police directorates and the Cobra task force conducted 15 house searches of 20 people and in five instances, searches were conducted with the consent of the suspect. A total of 20 firearms and numerous other weapons, such as a dagger with SS runes, four samurai swords, five sporting bows, three nunchakus and a butterfly knife as well as electronic data carriers and Nazi devotional objects were confiscated.54

Also in 2018/2019, a high-profile case was investigated. This related to a network called the “Staatenbund Österreich” which maintained a structure of individuals and subgroups called “confederates”. Following the investigation of the group’s leading figures, 14 people were put on trial in Graz for treason and the attempted formation of an anti-state association.55

During the COVID-19 pandemic, conspiracy theorists in Austria became increasingly prominent and formed alliances with the far-right milieu.56 In 2021, Chancellor Karl Nehammer referred to the growing threat of “unholy alliances” that were disbanded or strengthened at demonstrations critical of the COVID-19 restrictions. However, the planned storming of the parliament in Vienna, which was part of one of these demonstrations, was prevented by the Austrian security authorities.57

The current Minister of the Interior, Gerhard Karner, warned that during such demonstrations, right-wing extremists, hooligans and even individuals that were previously unconnected to the extremist milieu came together and tried to infiltrate demos. Many of the supporters reportedly also sympathized with a coup d’état.58

The activities of “Objekt 21” seem to continue in the year 2022, as the former leader of the group was recently accused of Wiederbetätigung (continuing the operations of the banned group), as well as crimes related to weapons’ legislation. Concretely, the individual was involved in the selling of weapons and NS devotional objects.59

Another area in which VRWE and OC intersect is the hooligan scene, such as for example the sports community Noricum, whose members originate from the hooligan scenes of the teams SK Rapid Vienna and FK Austria Vienna. Since 2015, their involvement was regularly observed at Identitarian demonstrations. Some members of Noricum also have tattoos with right-wing extremist symbols.60 Members of this group are active in martial arts and work as bouncers, both with links to the red-light milieu. They also maintain contacts to biker clubs and debt collectors, among others. The Identitarians were reported to try to specifically recruit people from this scene. Direct connections have been established to the OC bikers club United Tribuns (UT), active in forced prostitution and human trafficking.61 UT was banned in Germany but a number of chapters also exist in Austria and criminal proceedings were conducted against some of its members on charges of extortion, coercion and aggravated robbery.62 A successful police raid found evidence of cocaine and cannabis trade by members of UT in Austria.63 Multiple members of Noricum also appear to have personal ties to individuals from the Viennese chapter of the Hells Angels.64

During the past few years, several cases demonstrated a distinctive pattern. Police operations repeatedly uncovered illegal weapons caches and illegal weapons trade activities by VRWE actors, financed through the trade in illegal drugs by these VRWE actors. Such VRWE activities were geared towards building a right-wing extremist militia in preparation for the so-called Day X.65 For example, in December 2020 a high number of automatic and semi-automatic weapons as well as explosives and other objects were confiscated as a consequence of a police operation targeting drug-related criminality (in particular with amphetamine, cocaine and marihuana).

Concretely, it was reported that: “The proceeds from the drugs were used to buy Uzi, AK47, Skorpion submachine guns and assault rifles and ammunition.” The ultimate purpose was to build a right-wing extremist militia.66

Another police operation in November 2021 found another large weapons arsenal of a right-wing extremist couple. This case is connected to a network of right-wing extremists in Germany and Austria. The main suspect was already convicted on counts of Wiederbetätigung and was member of the VAPO (Volkstreue Außerparlamentarische Opposition) which had formed around the prominent and well-known Neo-Nazi Gottfried Küssel.

Furthermore, media reports stated that between 2019 and 2020, 20 illegal weapons arsenals were discovered in the right-wing extremist scene in Austria alone.67 These weapons arsenals included machine guns, submachine guns, sniper rifles, shotguns, handguns, explosives(TNT), ammunitions and Nazi-memorabilia.

Unfortunately, there is no publicly available information concerning the origin of the weapons seized in the various raids. It is also unclear whether the relevant authorities are currently investigating the matter. However, over the years, it has become clear that the Austrian neo-Nazi scene has close contacts with fascist structures of organized crime in the Western Balkans. The contacts are said to go back to the time when Austrian and German neo-Nazis fought alongside fascist Croatian militias as soldiers in the war in Yugoslavia.68 Huge stockpiles of weapons exist there to this day. Therefore, this is likely one of the sources from which this material is procured by VRWE actors in Austria.

The most violent incidents by VRWE actors yet not necessarily connected to OC in Austria in recent years include:

• 2016-2022:69 Prominent member of the international right-wing extremist HipHop scene and an administrator of hateful anti-Semitic website both convicted Philip H. (also known as “Mr.Bond”) made HipHop songs with national-socialist lyrics and distributed these online, that later inspired the German right-wing terrorist Stephan B. for his attack in Halle, as proven by the attacker’s use of a “Mr.Bond” song during his livestreamed attack. The suspect also translated the right-wing extremist manifesto of the Christchurch attacker, and later dedicated a song to him. Philip H. praised online the right-wing extremist murderer of the German politician Walter Lübcke as well. During a house search, authorities found weapons and Nazi memorabilia at the suspect. His brother, Benjamin H. was found to be behind the anti-Semitic website “Judas watch”, known for inciting hate against Jews and creating a public list of ideological “enemies”. Both were convicted in the first instance, but the decisions are not final.

• 2021:70 Thwarted terror plot of an Identitarian/DO5-member with pipe bombs A 78 years old man was charged and convicted after he disseminated national-socialist sentiments on social media while also cultivating drugs in an indoor space and selling these. During a search at the suspect’s house, authorities found guns, ammunition, war memorabilia, merchandise of the Identitarians and DO5, ingredients and handwritten instructions for the construction of pipe bombs, as well as other means necessary for the preparation of a right-wing terrorist crime.

- In October 2017, Friedrich F. allegedly murdered his two neighbors and injured another person near Graz. F. is currently a fugitive. He was active in the extreme right-wing scene in Styria.71

- In May 2016, a 27-year-old in Nenzing, Vorarlberg, apparently randomly shoots two people with a submachine gun at a concert and injures a dozen more. He then killed himself. The perpetrator had close contacts with the neo-Nazi terror group Blood and Honour.72

- In March 2009, a neo-Nazi and martial artist beats his victim Albrecht M. to death on Vienna’s Rotenturmstrasse.73

The banning of right-wing extremist organizations is a rare occurrence and only the more prominent ones such as the Identitarians are targeted. Once individuals have been convicted to jail sentences of extremist or terrorist offences in Austria, they become subject to continuous surveillance by security authorities in prison.

In such cases every contact in and out of prison and also with other inmates is documented by a special branch of the ministry of justice, specialized in terrorism and extremist offences. This part of the ministry of justice was established in 2022 as reaction to the terrorist attack in 2020.74

Employees of the military counterintelligence office warned in 2019 of an extreme right-wing terror cell within the Austrian Armed Forces.75 Investigations into this began after the Hannibal Network was uncovered in Germany. The Hannibal Network is linked to the far-right association Uniter, which expanded its activities to Austria in 2019.76

According to a 2019 investigation report by the authorities, it appears that every fifth person of the Identitarians legally owns a firearm. Ten members of the movement are subject to an ongoing weapons ban. Some are also said to have violated weapons bans.77

There is a relatively large degree of exchange between the individual extremist scenes or groups within the overall right-wing extremist milieu and also similarities in terms of content and organization, as can be seen in the examples of the Identitarian Movement and the DO5.78 Also, through the strategy of certain groups and networks operating under multiple names, the groups try to appear bigger than they actually are.79

Also, as can be seen in the most recent public report of the DSN, the COVID-19 crisis has brought long-standing leading cadres of the domestic organized right-wing extremist scene into the limelight and they have been able to use their structures and networks again, in some cases to make appearances at public demonstrations critical of the pandemic-related restrictions.80

The intersection between the right-wing extremist scene and organized crime can be seen most clearly in the cases relating to the various weapons caches found in recent years. The investigation of cases at the nexus between OC and VRWE usually takes place at the level of the state criminal police and starts with investigations into OC activities. Drawing on publicly available information, it also appears that specific investigations targeting the VRWE aspects of such cases are scarce. According to Chancellor Nehammer, the network uncovered in 2020 showed connections between the right-wing extremist area and organized crime under the name of “Miliz der Anständigen” (Militia of the decent), albeit recent reports and the charges brought by Austrian prosecutors indicate that it might be less of a well-structured network than initially presumed.81 The financing for the purchases of these illegal weapons and ammunition by VRWE actors in Austria was provided through proceeds from the trade in illegal drugs. According to Chancellor Nehammer, this type of financing was previously known primarily from the jihadi terrorism scene in the country. The fact that this type of financing is also used for right-wing extremist terror was not really known in Austria before this incident. “This model of terror is obviously also followed by right-wing extremist terror,” said the Chancellor. In general, he said, there was strong connection between the neo-Nazi scene and newer groups such as the “Reichsbürger.”82

Therefore, in conclusion, the cases outlined above demonstrate that there is a connection between VRWE actors and OC in Austria. On the one hand, this relates to the trade in illicit drugs, although it seems that Austrian VRWE actors appear to be directly involved in such activities without acting as a distributor for OC networks.

In addition, it seems likely that Austrian VRWE actors have connections to fascist OC structures in former Yugoslavian countries and that these were one of the sources from which the illegal weapons and ammunition seized over the past few years from VRWE actors by Austrian security authorities were provided.83

Furthermore, there appears to be a notable overlap in membership between Noricum and UT as well as MC. The provisions of security services is characteristic to both organizations. In other words, the roles of VRWE and OC actors cannot be clearly distinguished, as multiple individuals are engaged in both circles.84

Case study

“Objekt 21” was an Austrian VRWE organization founded by members of the VRWE group Blood and Honour in 2010. It was disbanded by authorities in 2011, yet some parts were secretly active until 2013. Operating in Upper Austria, the group established a cultural association as an official front for their activities, registered under the address of a building that the group bought. “Objekt 21” was known to engage in a variety of activities. Initially these primarily focused on the organization of rock concerts. Based on official estimates by Austrian authorities, the group had approximately 30 members and 200 further individuals that closely supported them.

Shortly after the establishment of the group, it forged connections to German OC and VRWE scenes. In particular, they cooperated with biker gangs (Hells Angels Germany)85, the “Freie Netz Süd” (FNS) in Bavaria, and the Aktionsgruppe Passau.86

To fund their activities, “Objekt 21” engaged in arson, burglary, violence, kidnapping, extortion, robbery, illegal arms and drugs trafficking, and was also involved in illegal prostitution.87 “Objekt 21” primarily served as the armed and violent partner of OC groups and networks, e.g. the members acted as the muscle of these criminal networks to intimidate their rivals.88 The group’s leader as well as multiple members have since been convicted on a variety of crimes, including both terrorism-related charges and for organized criminality.89

TRENDS and STATISTICS

In 2020 the DSN recorded 895 right-wing extremist, xenophobic/racist, Islamophobic, anti-Semitic and unspecific criminal offences, as well as 1,364 reports (as compared to 1,678 in the previous year), with 801 (58,7%) being listed under the Prohibition Act (vs. 1,037 in the previous year).90 It is interesting to note that the 2020 annual DSN report does not contain information about connections between VRWE and OC.

In 2021, a right-wing terrorist attack by a member of the Identitarians/DO5 with homemade explosives was thwarted in Austria.91 In that year it was also announced that an annual public report focusing on right-wing extremism would be reintroduced after being suspended in 2002. The report is produced by the Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Justice, together with the Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance. However, the publication of the report has been delayed.92 Although the figures for 2021 were not included in the DSN report, they were published in response to a parliamentary question. Thus, the number of right-wing extremist crimes in 2021 had again risen sharply: 1,053 acts with a relevant background were recorded (previous year 895), 66 acts with a racist background (2020: 104), 52 anti-Semitic acts (2020:36) and nine Islamophobic crimes (2020:16). 102 were unspecific acts but attributable to the right-wing spectrum (2020: 42). The number of persons reported under the Prohibition Act has also risen sharply to 998, compared to 801 in 2020. The Ministry of the Interior sees the main reason for the increased numbers in the fact that the police and the executive authorities take their duties very seriously and therefore more reports are made due to increased deployment. However, experts, journalists and other members of parliament highlight that an increase also occurred in the absolute numbers of members in the right-wing scene in Austria.93

Regarding politically motivated crimes, authorities speak about a consolidation of the situation as compared to previous years (latest DSN report 2021 e.g.).94 The attempted terrorist attack in 2021 (see above) might indicate a potential qualitative change in the nature of the violence and the level of threat posed by right-wing extremism. Based on media information and the RTV dataset,95 there has been a clear increase in the number of cases involving the confiscation of weapons.

In general, the right-wing extremist scene in Austria in 2020 is also presented as “a potential danger relevant to state protection” according to the annual DSN report.96 Since 2019, there have been personnel changes. For example, long-standing leading cadres of the domestic scene (e.g. Gottfried Küssel, Martin Sellner) made public appearances again during the pandemic and attracted new followers. The right-wing extremist scene has established and far-reaching contacts in various underground scenes worldwide both on a personal level (marriage of Martin Sellner and Brittany Pettibone) as well as in terms of weapons procurement, in this regard, contacts also exist to organized crime networks (see cases above). The most recent developments in the right-wing extremist field can be seen, among other things, in the field of candidates standing for the 2022 federal presidential election: of the seven candidates, five either came from right-wing political spectrum or wanted to attract voters by using right-wing narratives.97

In both its 2020 and 2021 public report, the DSN assesses that supporters of the right-wing extremist scene now appear in part more violence-affine and also more violent, especially at demonstrations related to the COVID-19 restrictions.98 This resulted in a greater potential for conflict between right-wing and left-wing extremist milieus in Austria. This development was also highlighted in the 2021 DSN report: “It is evident that violence in the context of right-wing/left-wing extremism is not only directed against the ideological opponent, but can also affect third-party targets (the executive, private individuals, public and private property)”.99 The latest DSN public report published in 2022 assesses that the tensions between left-wing extremists and members of the DO5 in particular are unlikely to decrease in the near future due to the current economic and social situation in Austria.100

Legal and illegal FINANCIAL ACTIVITIES and NETWORKS

The nature of the overlap between right-wing extremism and OC was recently described by Austrian Chancellor Nehammer: “There is a dangerous mixture of organized crime and right-wing extremism here. If you think about that just the investigations into drug trafficking led to us being able to take this large number of weapons and explosives out of circulation. They sell and trade drugs and use the proceeds to buy weapons and explosives to destroy and shake up the free basic social order in the long term.”101

Furthermore, Austrian media also reported that VRWE increasingly resort to illegal prostitution to fund weapon purchases.102

Neo-Nazis are also increasingly using cryptocurrencies to disguise payment flows.

For example, experts believe that amounts in more than 75 different cryptocurrencies flowed as donations to Austrian right-wing extremist Philp H. (Mr. Bond).103 He has been in prison since 2021 for his anti-Semitic and Nazi-glorifying song lyrics.

In 2022, he was sentenced to a ten-year prison term. However, his sentence is not yet finally adjudicated.104